The pandemic has not yet reached the Saharawi refugee camps in Algeria. Despite that, the people in the camps live in isolation. The Saharawi are famous for their hospitality and welcome even in difficult times, something that makes it even harder to adjust to the new practices of social distancing and confinement, writes the artist Mohamed Sleiman Labat who lives in the camps.

The Saharawi Refugee camps located in the southwest part of the Algerian desert called Hamada are one of the last remaining places on earth where Corona Virus has not set foot. But the consequences of the lock down may be severe. The camps host over 170 thousand Saharawi since 1975 following a 16-year war in their homeland of Western Sahara, now largely occupied by Morocco. There are five main camps spread about in the area near the city of Tindouf in Algeria.

The Saharawi authorities in the camps have ordered the closure of the camps to the outside world; movement between the five camps themselves is also highly restricted. Such prevention policy is probably the best option that the Saharawi have, given the fragile medical system in the camps despite the strong efforts from the local Saharawi doctors and nurses. Last week, the Algerian authorities set up a field hospital to avoid Saharawi patients to travel to Tindouf, now hosting 14 confirmed Corona cases. A national committee of Saharawi doctors and health workers was established in March. The committee assesses, evaluates and makes decisions about the situation in the camps’ hospitals and ways to prevent overload among other responsibilities. The Saharawi ministry of Public Health together with filmmakers and artists from the Saharawi Film School and other groups launched a series of media campaigns using videos and social media outlets in Hassania to help explain one-to-one to the people in the camps the Corona situation and the prevention measures.

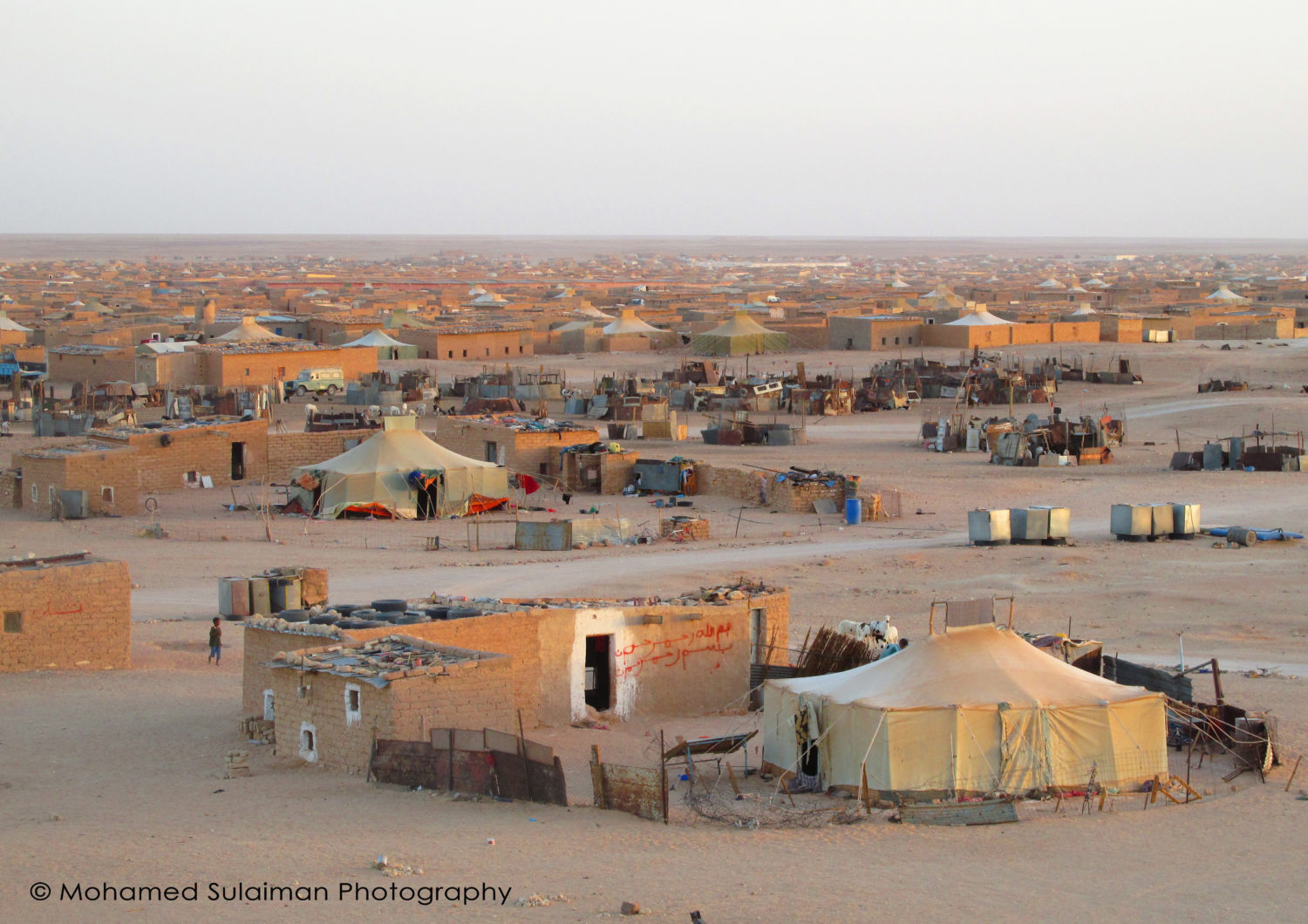

The refugee camps have been in this area for four decades now. The Saharawi built schools, hospitals and other administrative facilities, but they have been living in fabric tents and mud houses. The camps are developing into city-like structures with paved roads connecting the camps, newly introduced electricity and Internet access. The whole camp population is still dependent on international food aid through the UNHCR. Small emerging markets are starting to slowly contribute to the local economy but with the high rates of unemployment, a lot of people cannot afford to secure food on their own.

The prolonged displacement may have caused acute physical disconnection with their ancestral nomadic lifestyle and the place they call home, yet the Saharawi seem to have maintained a strong culture and identity still alive today. The Saharawi are famous for their hospitality and welcome even in difficult times. While some of these traditions and social habits are firmly built upon close interaction and sharing, it is even harder to adjust to the new practices of social distancing and confinement.

Corona virus may not have hit the Saharawi in the camps as the Saharawi and Algerian health authorities have not announced any cases there but the impact of the lock down is starting to appear. Doctors, engineers, researchers and artists are looking into ways to respond the Covid-19 impact on the everyday life in the camps. Food and water distribution delays especially during the summer are particularly alarming. A number of initiatives have been circulating on different social media platforms. Many debates are addressing post-corona situation, food sovereignty, sustainable alternatives and local solutions. Vulnerable communities such refugee camps have quickly disappeared from the pandemic discourse despite the fact of being in the risk groups. The situation is frightening sometimes, but the potential of a different breakthrough not by a medical vaccine, but by a new set of practices, may alter the fate of the Saharawi on many levels.

Taleb Brahim is a leading Saharawi agricultural engineer working on developing small-scale family gardens to help Saharawi families produce their own food. The conditions are very challenging in the desert. Shortage of water, poor soil and exposure to extreme temperatures are concrete obstacles he is keen to fight. A number of farming practices such hydroponic and aquaponic gardening has been part of his experiments. The challenges seem to open ways for solutions that can alter the fate of the Saharawi. Gardens producing food for the Saharawi in the desert is changing the narrative of the refugees and changing the refugees themselves. The Saharawi have been nomads for centuries; a community on the move that never settled down to grow anything. But with the new gardening practices, they could start their first steps towards food sovereignty.

Mohamed Sleiman Labat

Saharawi artist, Motif Art Studio