Ali Alabdallah is a Syrian writer and activist in Sweden. Katsiaryna Lutsevich is a journalist from Belarus who was also forced to flee. Here they talk about what it’s like to write from exile – and constantly hope for change.

Ali Alabdallah, a Syrian writer and activist in Sweden, shared the story of his exile from his homeland and his own view on the future of the Syrian diaspora in Sweden. His story resonates with the story of Belarusian journalist in exile Katsiaryna Lutsevich, emphasizing the universal struggle for freedom of speech and the preservation of national identity in the new conditions.

Katsiaryna: Hello, Ali! As a Belarusian journalist in exile, who was forced to flee her homeland, I’d like to talk to you about our similar experiences. What’s it like for you to become an exile?

Ali: What forced me to flee Syria was the Syrian war, which began with peaceful demonstrations in 2011, but later turned into a war between the Syrian opposition and the authoritarian Syrian regime, supported by Russia and Iran. What compelled me was the regime’s excessive use of violence against the Syrian people to suppress the protests, turning Syria into a scene of chaos, killings, and bombings that affected everyone.

I was working as a journalist in Syria, and I was at constant risk of arrest, which pushed me to flee as quickly as possible to avoid being detained by the Syrian intelligence services. They had begun contacting the state-run Al-Baath newspaper, inquiring about me. This created a state of fear and terror for me, leading me to make the decision to seek asylum in Sweden.

Katsiaryna: Can you tell me more about your life in Syria before you left? What risks did you face there as a journalist?

Ali: I worked as a journalist in Damascus, the capital, since graduating from the College of Media in 2008, contributing to various newspapers, magazines, as well as radio and television. The last media outlet I worked for was Al-Baath, the Syrian newspaper affiliated with the ruling Baath Socialist Party in Syria.

One of my colleagues at the newspaper wrote a report about me, accusing me of cooperating with the Syrian opposition, spreading false news, and planning to escape from Syria. This report was sent to the Syrian security services, which led the intelligence to contact the newspaper where I was employed. Fortunately, I was informed by another colleague at the same newspaper that the Syrian intelligence was pursuing me. This prompted me to make the decision to flee Syria in order to avoid imprisonment.

Katsiaryna: I also faced the risk of imprisonment in my homeland. As a journalist, I wrote articles about the discrimination against the national language. One of these articles caught the attention of a pro-Russian activist, notorious for filing complaints and targeting Belarusians who opposed Russian influence. Many individuals were imprisoned as a result of her actions. For my own safety, I was forced to change my name in my articles and eventually leave Belarus. After a meeting between Belarusian authorities and Russian security representatives in 2023, all Belarusian cultural NGOs were labeled as extremist formations. That’s why I couldn’t return to my country.

Tell me, how was it for you to live under Russian influence?

Ali: The Russian regime supported the Syrian regime for 50 years, up until Bashar al-Assad came to power in 2000. Russian military support for the Syrian regime increased after the start of the Syrian revolution in 2011, especially after the revolution was forced to arm itself for self-protection. The Russian regime supported Assad with weapons and air power, beginning with bombings of Aleppo, the Damascus countryside, and other Syrian cities where armed Syrian opposition forces were present.

This led to the martyrdom of thousands of Syrian civilians, including women and children, and caused the displacement and forced migration of millions from Syrian cities. The Russian influence has been significant, as without Russian support, Assad would not have been able to remain in power throughout the 14 years of war. The Syrian people were deeply discontented with this support, and many suffered immensely, losing numerous members of their families.

I was forced to flee Syria for reasons related to my personal safety and the dangers of war, as missiles and explosions were raining down on my native place, Damascus. I chose Sweden because it is a safe country with a strong economy, which offers opportunities for personal growth.

Katsiaryna: As political migrants, we both feel struggles to adapt to the new conditions and at the same time to preserve our own identities. What’s the role your national identity plays in your life? Is it important for you?

Ali: I am a humanitarian refugee from Syria, and I have obtained Swedish citizenship. However, my identity remains both Arab-Syrian and Swedish. I feel a sense of belonging to both countries and take pride in being from Syria, the land of ancient civilizations, a country of coexistence, and a place of cultural, religious, and ethnic diversity. This diversity and peaceful coexistence are sources of Syria’s strength and beauty.

I still hold tightly to my Syrian identity and my sense of belonging to my homeland, Syria. This feeling of connection to Syria has only grown stronger after the fall of the dictatorial regime there.

In my daily life, I strive to convey the true image of Syria to Swedish society through my articles in Swedish or my contributions to Swedish media. My goal is to present a balanced and accurate picture of Syria, steering away from the negative focus on Islamic groups in Syria and the fear of Islam.

Katsiaryna: How has Swedish culture influenced you since your arrival? Do you feel that you’ve successfully integrated into Swedish society?

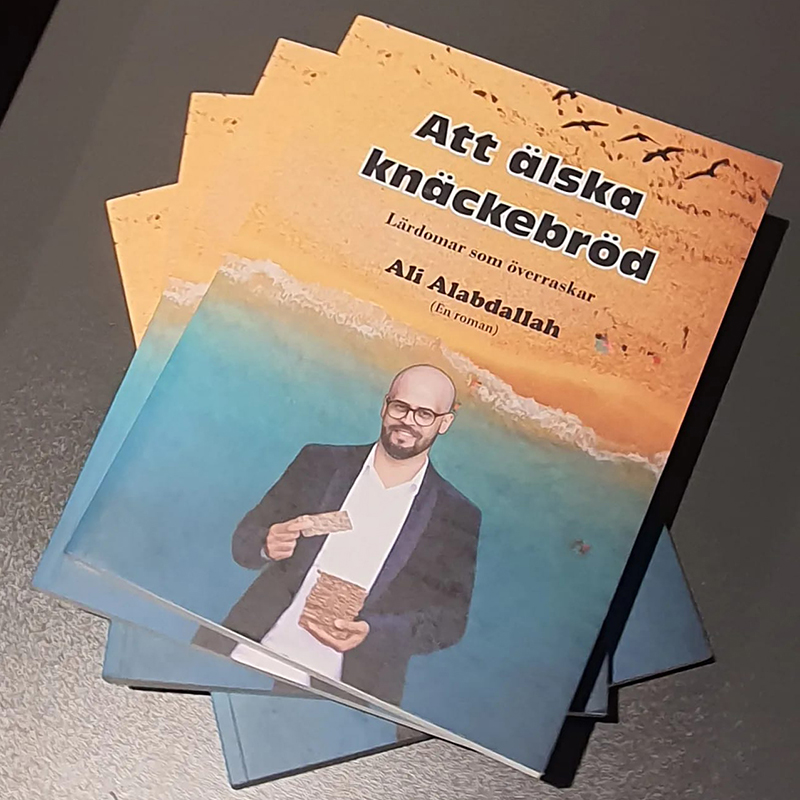

Ali: I learned Swedish quickly, found a job promptly, wrote four books in Swedish, and received two awards: the first was the Pluralism Prize in 2018, and the second was a cultural award in the city of Landskrona.

Talking about the Syrian diaspora, There are 150,000 Syrians who have obtained Swedish citizenship out of a total of 250,000 Syrians who came to Sweden. Many Syrians have higher education qualifications, and a significant number have at least secondary education. As a result, Syrians are currently among the largest groups of immigrant students attending Swedish universities.

I believe the integration of Syrians in Sweden is generally good, with some achieving very successful integration in terms of learning the Swedish language, establishing businesses, working in various sectors, purchasing homes, and more.

Unfortunately, many far-right parties in Sweden ignore this reality and attempt to focus on the differences between Swedish values and those of Muslim immigrants, portraying them as fundamentally incompatible with Swedish values.

Katsiaryna: How did you feel about living in Sweden, as a Syrian refugee?

Ali: I feel a full sense of citizenship in Sweden, which might be due to my open and flexible personality, as well as my emotional intelligence and social ability to interact with everyone with respect and adaptability. I arrived in Sweden in 2013, and now, after 11 years in the country, I have a good social and economic standing. Therefore, I do not feel like a refugee in Sweden, but rather I feel like an ambitious and successful person who belongs to two countries, Syria and Sweden.

Katsiaryna: In your opinion, how would the fall of the Assad regime impact the lives of Syrian refugees in Sweden? Do you think it might influence their decision to return to Syria?

Ali: If the situation in Syria stabilizes and it becomes evident that Syria is on a path toward further stability, I believe that many Syrians residing in Sweden will return to Syria. However, this is likely to apply more to those with temporary residence permits, as there is a significant possibility that the Swedish Migration Agency will not renew these permits. At the same time, I believe many Syrians will remain in Sweden because they have children enrolled in schools, jobs, properties, businesses, and even Swedish citizenship. There are approximately 150,000 Syrians in Sweden.

Katsiaryna: Unfortunately, Lukashenka regime showed its resilience in terms of sanctions. There is a sufficient support for the regime of Russia. We are neighbors, and that’s why it’s easier for them to intervene in case of the protests or any other form of national resistance. That’s why I still can’t return to my home. As long as Russia has the resources to control Belarus from within and support its hybrid occupation, I will not be able to return home because I will risk imprisonment.

Katsiaryna: Do you think it’s already safe for Syrians to return home?

Ali: It is too early to say that Syria has become 100% safe and stable. Many have started thinking about returning to Syria, especially those living in neighboring countries such as Jordan, Iraq, Turkey, and Lebanon. I believe many will return if the situation in Syria stabilizes.

However, they face significant challenges, as their homes are destroyed, and their cities lack the necessary infrastructure for living. Personally, I have started thinking about visiting Syria, but I don’t think I would settle there—perhaps in the future, if the situation becomes more stable and it is evident that the new Syria is on the path to democracy.

I am closely monitoring the situation in Syria and genuinely hope for a better beginning and future for the country. Everyone is tired of the war, and it is time for an inclusive political process in Syria that guarantees the rights of everyone.

Katsiaryna: Talking about the Belarusian case: Unfortunately, Belarus now is under Russian hybrid control. All institutions processed Russification and degradation. I can’t return to my homeland for political reasons. What about you? Are you planning to visit Syria in the near future?

Ali: Yes, I am currently considering a visit. Before the fall of the Syrian regime, it was impossible for me to visit Syria due to the oppressive security control and the risk of imprisonment, given that I am a journalist who fled Syria during the war in an irregular manner. The Russian role and influence in Syria are now non-existent after the fall of the fugitive president, Bashar al-Assad. The collapse of the previous regime also signifies the end of the Russian role in Syria.

Katsiaryna Lutsevich

Read also

|

Uppläsning av artikel

|