On 24 December, Ihsane El Kadi, editor-in-chief of the last free and independent media in Algeria, was imprisoned. Ihsane El Kadi is now threatened with seven years’ imprisonment, although no formal charges have been brought against him. And in EU there is silence.

Ihsane El Kadi was arrested by the Algerian security service after he reported that President Abdelmadjid Tebboune was planning to change the constitution in order to be re-elected for a new term. He also posted a tweet where he questioned the regimes claim that they had managed to ”recover” $20 billion that previously was lost in corruption. Ihsane El Kadi has earlier been sentenced to six months in prison for an interview he conducted with a banned organisation.

Since his arrest, Ihsane El Kadi has been transferred to one of the country’s prisons, but no formal charges have yet been brought against him.

As founder and editor-in-chief of Radio M and Maghreb Émergent, Ihsane El Kadi has been one of Algeria’s most influential journalists. The radio station and the newspaper have mainly targeted a young, urban audiences. The newspaper and the radio have become known for their criticism of the Algerian government as well as for giving space to progressive voices in the country and at the same time they invite government representatives to their platforms.

Among others, Nobel Peace price laureate Dmitry Muratov, has celled for his release.

In 2017, I was guided around the Algerian capital Algiers by Ihsane El Kadi. At the time, he had high hopes for change and development: the harsh oppression had begun to subside and Ihsane El Kadi saw a time when tourists would be able to come to the closed country and visit the neighbourhoods of the capital Algiers, that was made immortal by the film The Battle of Algiers.

Two years later, in 2019, protests exploded in Algeria through the Hirak movement. The regime was forced to open up. After President Abdelaziz Bouteflika was forced to resign due to demands for democratic reforms and a change of government, Abdelmadjid Tebboune was elected president.

However, the situation soon deteriorated again and more and more journalists and activists were imprisoned. In 2021, most of the country’s independent media were shut down and several foreign media companies lost their licenses to operate in the country.

Today, many of the country’s activists and journalists are behind bars and Algeria has more than 300 political prisoners. In April 2022, Hakim Debazii, one of the leading figures of the Hirak movement, died in prison. On the Freedom House list of countries, Algeria is classified as a non-free country and with the last free media outlets now closed, some 30 journalists are also losing their jobs.

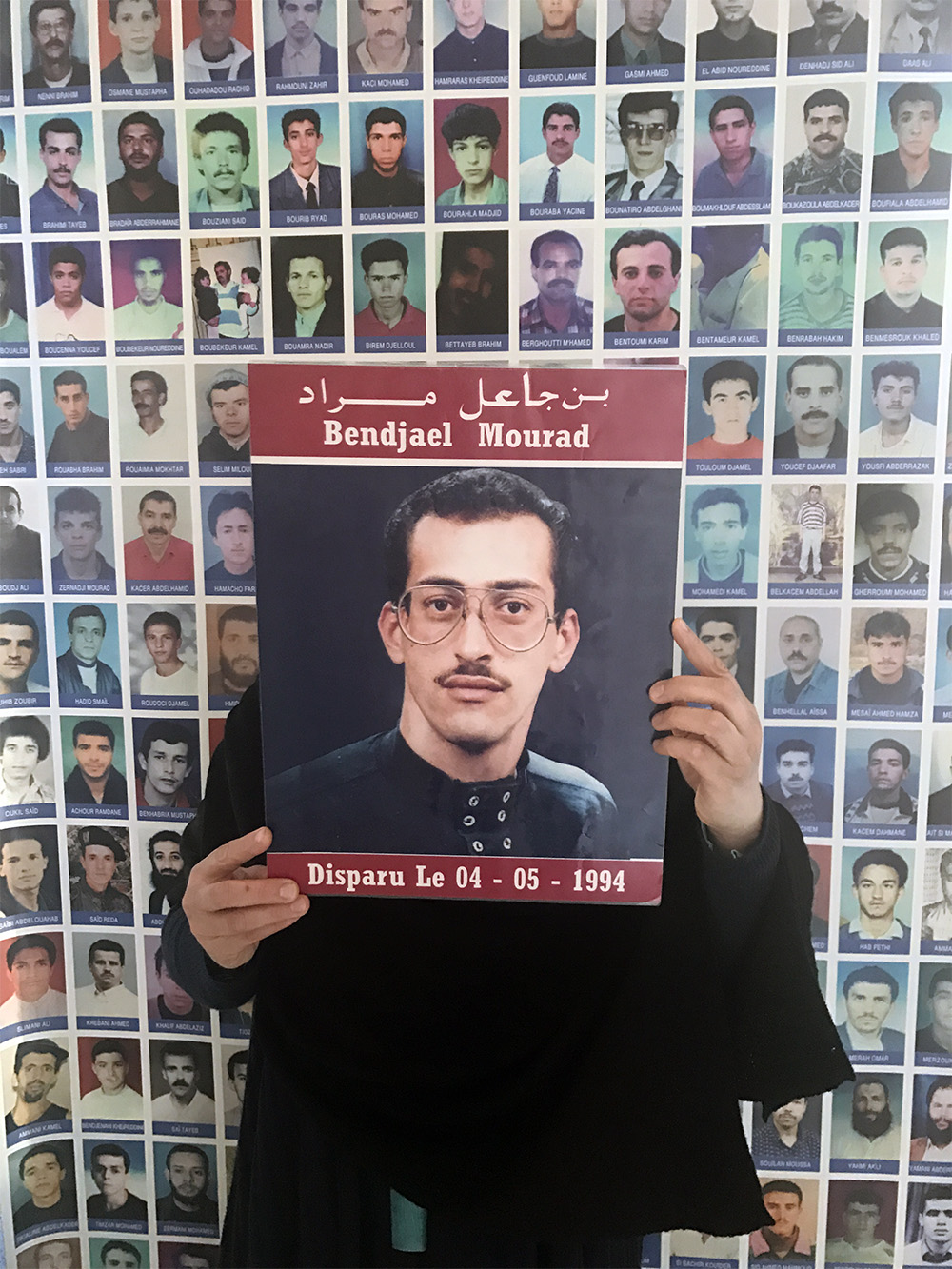

Ever since the bloody war of liberation from France, Algeria has been a more or less closed. In the 1990s, Algeria was marked by a bloody civil war that, in many ways, was an early version of the similar conflicts that later flared up between governments and Islamist groups in other countries in the region.

The conflict began when the Islamist FIS party won the 1992 elections, but its victory was not accepted by the government of the day. This led to violent protests, and soon the civil war between the government and Islamist groups was a fact. The conflict turned very bloody, with thousands of deaths on both sides. The government used military force to suppress protests and Islamist groups used violence and terror against civilians to try to gain power.

The civil war ended in 2002 when most Islamist groups laid down their arms and the government made important changes to the country legislation, including giving more power to civil society. The conflict remains a sensitive issue as no one knows what happened to the thousands of people that was abducted.

Despite the increasingly deterioration regarding human rights and the fact that Algeria has close ties to Russia, the silence has been almost compact in Europe. The exception has been a group of EU parliamentarians who, in the fall of 2022, tried to raise the fact that Algeria has supported Russia in most UN polls since the invasion. The reporting from the country in the media is also very limited.

– The situation is worse than in many years, but we get no support from the outside. We are concerned that EU has chooses to turn a blind eye to what is happening in Algeria, since they need the gas and oil from here. The regime, which feels empowered, can therefore do whatever it wants without anyone caring, says an Algerian researcher who, for security reasons, asks to remain anonymous.

David Isaksson

Translated by Kajsa Sörman

Also listen too