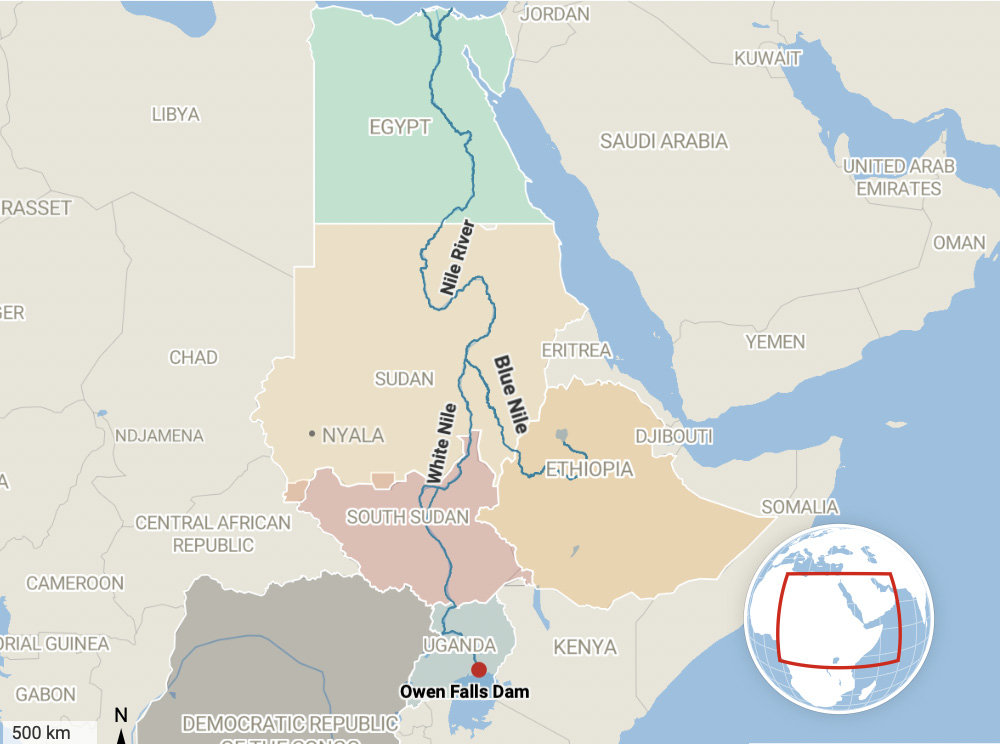

Uganda’s Owen Falls hydropower plan was supposed to help Ugandans utilise their own natural resource – the water in Lake Victoria. But, in the twisted logic of the empire, achieving this goal was constrained by London trying to achieve the British agricultural interests in Egypt, writes John Mukum Mbaku from Weber State University.

Uganda’s Owen Falls hydropower plant has a rich history that predates the country’s independence in 1962. The plant is located across the White Nile and sits between the towns of Jinja and Njeru on the shores of Lake Victoria. It is about 85 kilometres east of Kampala.

Uganda was a protectorate of the British empire from 1894 to 1962. In 1947, English engineer Charles Redvers Westlake recommended the construction of a hydroelectric dam at Owen Falls that was supposed to be East Africa’s largest power project.

The governor of the Protectorate of Uganda, Sir Andrew Cohen, wrote at the time that the Owen Falls dam would open new horizons of opportunity and prosperity for Uganda and all who lived there. Cohen went on to note:

Despite its technical complexity and the fact that we have had to draw upon skill and experience from many parts of the world, it belongs to Uganda and to Uganda’s people. The power which the dam will provide and the industries it will make possible will bring solid benefit to everybody in the shape of increased wealth; above all, it will bring new opportunities to Africans.

At its completion in 1954, the dam immediately expanded Uganda’s electricity supply capacity from 1MW to 150MW. But the expected boom in electricity consumption didn’t happen. One textile mill and a copper smelter were the only industrial establishments to crop up.

The Uganda Electricity Board (UEB) – which was established on 15 January 1948 – resorted to selling between one third and one half of the electricity generated to Kenya.

The institutional arrangements for constructing the dam left a damaging legacy that is still felt today. The British established governance arrangements for Nile waters that effectively granted Egypt veto power over all construction projects on the Nile. This legal regime continues to cause conflict between Nile riparian states to this day.

Owen Falls’ construction has to be seen as part of a racist colonial project, the sole objective of which was the exploitation of peoples and their resources to maximise British interests.

Empire’s twisted logic

At the end of World War II there were protests throughout the British empire as demands for independence began picking up pace.

In Uganda, the country’s new colonial governor, Sir John Hathorn Hall, was forced to take action. Some of the steps he took were informed by the need for the colonial government to show restless and poverty-stricken Ugandans that it was interested in promoting economic growth, industrialisation and development.

The dam was supposed to help Ugandans utilise their own natural resource – the water in Lake Victoria – to provide themselves with a significant level of energy independence.

But, in the twisted logic of the empire, achieving this goal was constrained by London trying to achieve interests elsewhere. In this case, British agricultural interests in Egypt.

In 1929, Egypt and Britain had signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, which was designed to harness the waters of the Nile River and its tributaries to produce raw materials, notably cotton, for British industries.

The treaty, which created what are today known as historically acquired rights, was concluded without input from Uganda or other Nile riparian states.

These rights allocate virtually all Nile waters to Egypt and Sudan. They also grant Egypt veto power over all construction projects on the Nile River and its tributaries.

As Ugandans would later find out, the British had, without their permission, placed Egyptian officials in a position to veto development projects in Uganda and other upstream Nile Basin states.

Despite the fact that the Owen Falls dam was to be constructed on the White Nile in Uganda, Uganda was forced to obtain permission for its construction from Egypt.

Source of tension and conflict

The 1929 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty and the 1959 Nile Treaty – which was a bilateral agreement between Egypt and Sudan – continue to fuel conflict between the downstream and upstream states in the Nile Basin.

In fact, Ethiopia’s refusal to abide by and be bounded by these colonial anachronisms has forced officials in Cairo to threaten to go to war to maintain Egypt’s acquired rights.

In accordance with the spirit of the 1929 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, colonial Uganda was forced to submit the documents for constructing the Owen Falls dam to Cairo for approval.

The construction of the dam would be the responsibility of the UEB, which was also to administer and maintain the project. However, the interests of Egypt were to be represented at the construction site by an Egyptian resident engineer, who would instruct the UEB on the discharges to be passed through the dam.

It is no wonder that when Ethiopia announced its intention in 2011 to construct a dam on the Blue Nile, Egypt sought similar concessions. Just as it had demanded of colonial Uganda, Egypt sought to maintain technical staff at the site of Ethiopia’s dam to monitor its operations.

Racism on site

The racist foundations of colonialism were quite evident at the Owen Falls dam site. For example, after estimating that the job would require a labour force of 2,000, the UEB built labour quarters for Europeans and Asians, complete with a club, community centre and swimming pool, at the Amberly Estate north of Jinja.

But it chose to house all African staff in quarters located across the bridge in Njeru.

These discriminatory economic and social policies would spill into the post-independence period and be exploited by dictator Idi Amin for his personal interests.

When she died on 8 September 2022, some Ugandans remembered Queen Elizabeth II as the young monarch who, in 1954, inaugurated the Owen Falls dam as a symbol of energy independence and ushered in a new era of industrialisation and economic development in Uganda.

But others remember her as the person who, over 70 years, presided over a country that reminds them of brutal exploitation, including the theft of their resources.

John Mukum Mbaku

Professor, Weber State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.

Read also