The German Kaiserreich was at the beginning of the 20th century the fourth biggest colonial power and the first genocide of the 20th century was committed by Germany in today’s Namibia. Despite this, colonialism was widely degraded to a mere footnote of German history, writes Henning Melber.

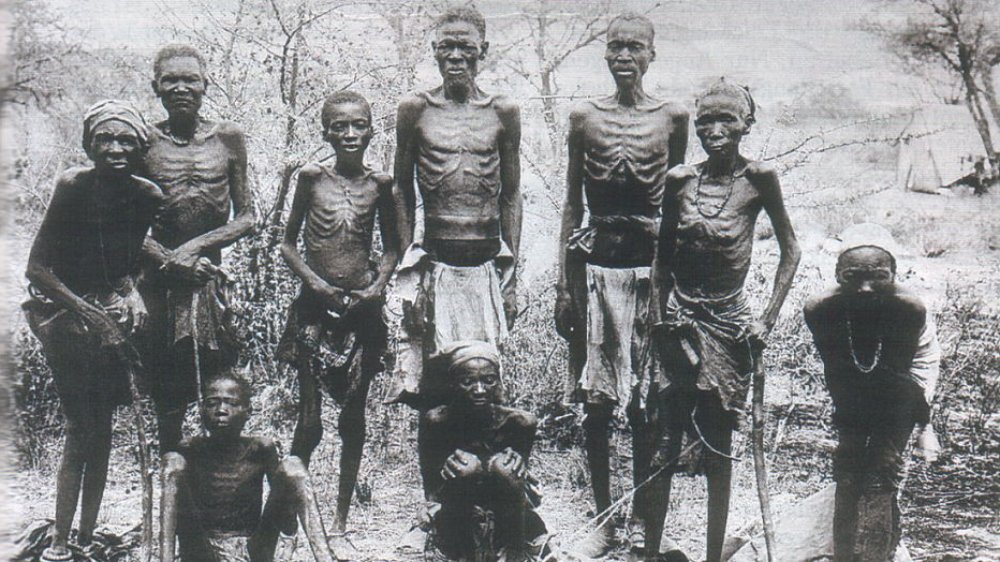

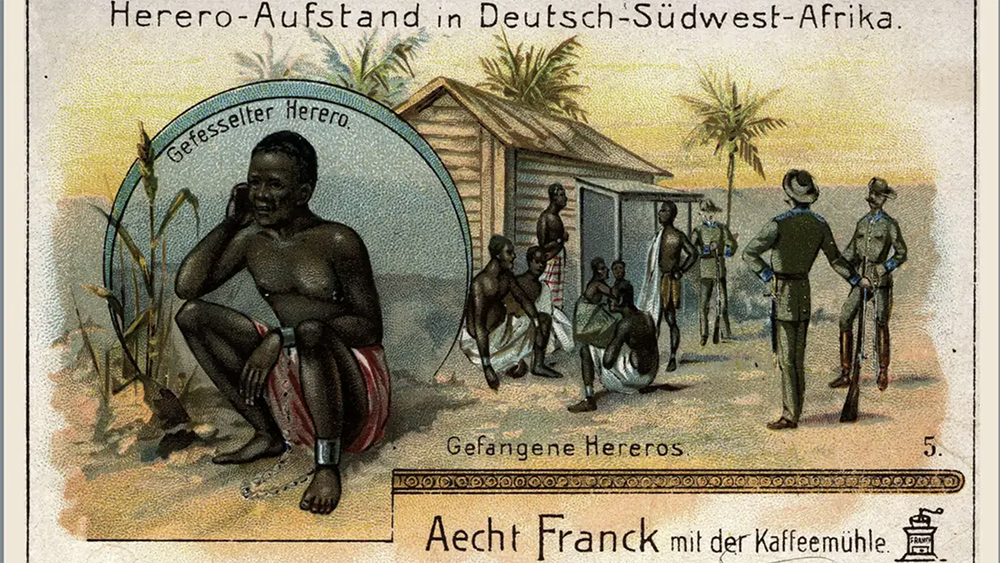

The German Kaiserreich was at the beginning of the 20th century the fourth biggest colonial power. Since 1884 it declared South West Africa, Togo, Cameroon, East Africa and some South Sea Islands (including Samoa) as its property, to which it added the Chinese lease territory Tsingtao. Hundreds of thousands colonised mainly in East Africa lost their lives through colonial violence. The first genocide of the 20thcentury took place in South West Africa, where an estimated two third of the Ovaherero, a third of the Nama and numerous Damara and San were deliberately killed with lasting consequences for the descendants of the victims until today.

Ending with World War 1, colonialism was widely degraded to a mere footnote of German history. In West Germany it was mainly perceived through uncritical lenses. In East Germany the colonial archives and the support of the anti-colonial struggle fostered a critical historiography. As different as these engagements were, they had no impact on a memory culture among the wider public in both countries.

This changed since reunification. Civil society made inroads in the public discourse. Post-colonial initiatives, Afro-Germans and scholars engaged with the brutal forms of German colonialism. They all managed to obtain some media coverage and entered mainstream debates, if only with limited impact. But it opened new frontiers of who is entitled to engage how and best.

Modest inroads

In 2015 the German government admitted that the warfare in South West Africa was genocide from today’s perspective. German Namibian government negotiations resulted in a controversial Joint Declaration not yet adopted. This created increased debates how to come to terms with the past in the present.

The so-called traffic light coalition (Ampelkoalition) of the Social Democrats (SPD), the Greens (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen) and the Liberal Party (FDP) declared in its coalition agreement of December 2021 the reconciliation with Namibia an indispensable task of historic and moral responsibility. It committed to tackle as part of its cultural politics colonial continuities. But except an intensification of provenience research and the restitution of some looted artefacts (notably a few Benin bronzes) and human remains little happened.

In response to an interpellation, a sober self-critical diagnosis of 31 October 2024 concedes that Germany’s colonial past has been for decades a non-theme in politics and society and was wrongly so pictured as relatively harmless because of its short duration. That this changed in recent years was attributed to civil society. It admits that the treatment of Germany’s colonial past remains a task still at the beginning.

A belated attempt by the state minister for Culture and Media in the Office of the Chancellor tried in 2024 to add to the framework concept of memory culture (Rahmenkonzept Erinnerungskultur) colonialism to the pillars of the Nazi-regime and the GDR. But it also suggested a fourth pillar on migration. Since the official memory culture has an exclusive focus on state-responsible injustices, the proposal failed. A final effort to rescue the colonial dimension by deleting migration came too late as the coalition had by then collapsed.

Reactionary roll back

The new discourses provoked colonial-apologetic revisionism rejecting post-colonial efforts as a “guilt complex”. A draft resolution submitted by the right-wing Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) to Parliament in December 2019 argued that German colonialism contributed to the liberation of the African continent from archaic structures. It called on the government to develop a commemorative culture that acknowledged the beneficial aspects of the German colonial era; to promote such perspectives in school curricula; to decisively oppose demands for reparations; to refuse the restitution of cultural goods merely for reasons that the colonial times were “criminal”; and to appeal to communities in the federal states to maintain street names which memorialised colonial personages and places.

It attacked ‘cultural Marxist inspired post- and de-colonialism’ and bemoaned a paradigm shift since German unification, creating the impression that critical colonial-historical studies had since then been indoctrinated by East German ideology. It accused the ‘left spectre’ of having imposed its ‘normative interpretation of the past’ as the dominant view and of having turned those sympathetic to the idea of a colonial civilising mission into victims.

The Konrad Adenauer Foundation has since on its Public History Portal Geschichtsbewußt introduced a thematic focus headed ‘Postcolonialism: attack on the West’ (Postkolonialismus: Angriff auf den Westen). In its introduction it warns that postcolonial criticism of an enlightened universalism and the West is a threat to social cohesion. This is indicative for the new cultural policy as declared in the election campaign of early 2025. Just like the AfD, the CDU and CSU reanimated in their cultural-political orientation the term lead culture (Leitkultur).

Relegation of colonial memory

The current government of CDU/CSU and SPD entered in May 2025 a coalition agreement. It deals with colonialism in three sentences. Namibia is not mentioned any longer. It declares to keep an eye on creating a dignified place of memory for dealing with colonialism, but there is no mention of this under memorials or elsewhere. Such initiative would be a task for Wolfram Weimer, appointed as State Secretary for Culture and Media in the office of the Chancellor.

In a book declared to be a conservative manifesto, he had listed ten commandments of a new civility (Bürgerlichkeit). The preface qualifies it as a critical new positioning of old values. He affirmatively refers to Oswald Spengler’s Der Untergang des Abendlandes (The Decline of the West or The Downfall of the Occident) of 1918. For him multiculturalism requires a reminder that the good old things still exist. He rebukes the ‘do-gooder-patronisers’ (Gutmenschen-Bevormunder) and ‘moral know-it-all’ (moralische Beserwisser) for a loss of substance in a funfair society (Jahrmarktgesellschaft).

In an article after his appointment, Weimer opinionated that cultural wars are rarely about culture, but over the power of definition, ideas and perspectives. This echoes a opinions in the dossier by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, which accuses postcolonialism to discredit eurocentrism and the legacy of European enlightenment as Western cultural imperialism. Asked in an interview if adding colonialism to official memory culture is dangerous relativism, Weimer responded in the affirmative. He points out that for the ethical backbone of the German State the Holocaust is a singular reference point. In September 2025, Weimer presented his new state memory concept, in which colonialism is not mentioned.

Using the Holocaust as argument to disrespect in official memory culture other forms of trauma caused by mass violence of the German state creates a calendar with the Holocaust as first breach of civilisation (Zivilisationsbruch) in denial of earlier uncivilised acts. Not by coincidence reminds Hannah Arendt of the practices in the German colonies and the mindset of the perpetrators as seeds, which were bearing fruits in the Nazi regime. The otherwise admirable willingness to face the responsibilities for the Holocaust has, as Pankaj Mishra observed, de-sensitised towards other forms of mass crimes. Such selectivity by omission is tantamount to memory failure.

Henning Melber

Associate of the Nordic Africa Institute in Uppsala and an Extraordinary Professor at the University of Pretoria and the University of the Free State in Bloemfontein.

The article is based on a presentation held at a conference by Historians Without Borders on ‘Narratives of Power: Memory Politics in Russia, Germany and the Contemporary World* held in Potsdam on 28 October.

Read also

|

Uppläsning av artikel

|