German and Swedish society alike tend to neglect or ignore the active participation in overseas slave trade. Little if any is on record in the official public memory and discourse. In his new book, The Long Shadow of German Colonialism, Henning Melber addresses the prevailing colonial amnesia.

German and Swedish society alike tend to neglect or ignore the active participation in overseas slave trade. Little if any is on record in the official public memory and discourse. Similarly, the anthropological racist classification of humans on a scale from primitive to civilized, promoted also by Carl von Linné, remains largely hidden. As a historical chapter of the mythology of race, it is rather forgotten than actively tackled as an ideological justification of colonial rule. The similar role of Swedish anthropologists at the beginning of the 20 th century to elevate in cohorts with German Arian obsession the Nordic race as “a natural aristocracy” remains another deliberately neglected chapter of Swedish involvement in Europe’s expansion based on self-declared white supremacy (a term only introduced recently, but a reality practised since long).

Despite these overlaps – and putting aside the early Swedish colonial settlements in Delaware – the Swedish and German trajectories took different turns. While Sweden in the first half of the 20 th century focused on a domestic policy giving priority to a social contract which laid the fundament for a welfare state, the German empire had after its formation in the 1870s an increasingly outward looking, imperialist aspiration accompanied by a history of violence. What started then and remains contested in the present is the focus of my book The Long Shadow of German Colonialism, of which a summary overview follows.

The German colonial empire

Imperial Germany was a late comer in the European run for colonies and the scramble for Africa. But catching up, land grab between 1884 and 1900 elevated the Kaiserreich into the top league of colonial empires at the time. South West Africa, Cameroon and Togo were in 1884 euphemistically proclaimed possessions under German protection, followed by East Africa in 1886, and a wide range of South Sea islands until the end of the 19th century. The lease of the Chinese Bay of Jiaozhou/Kiautschou was added in 1899 to the “collection”.

“Deutschland über alles”, German involvement in the Chinese “Boxer War” at the turn of the century disclosed the dominant mindset and signalled Germany’s ambition to play a leading role among the imperial powers. It was conducted with uninhibited brutality, and found its expression in the infamous Hunnenrede (Hun speech) by Emperor Wilhelm II when addressing soldiers despatched to China on 27 July 1900 at Bremerhaven: “Should you encounter the enemy, he will be defeated! No quarter will be given! Prisoners will not be taken! Whoever falls into your hands is forfeited. … may the name German be affirmed by you in such a way in China that no Chinese will ever again dare to look cross-eyed at a German.”

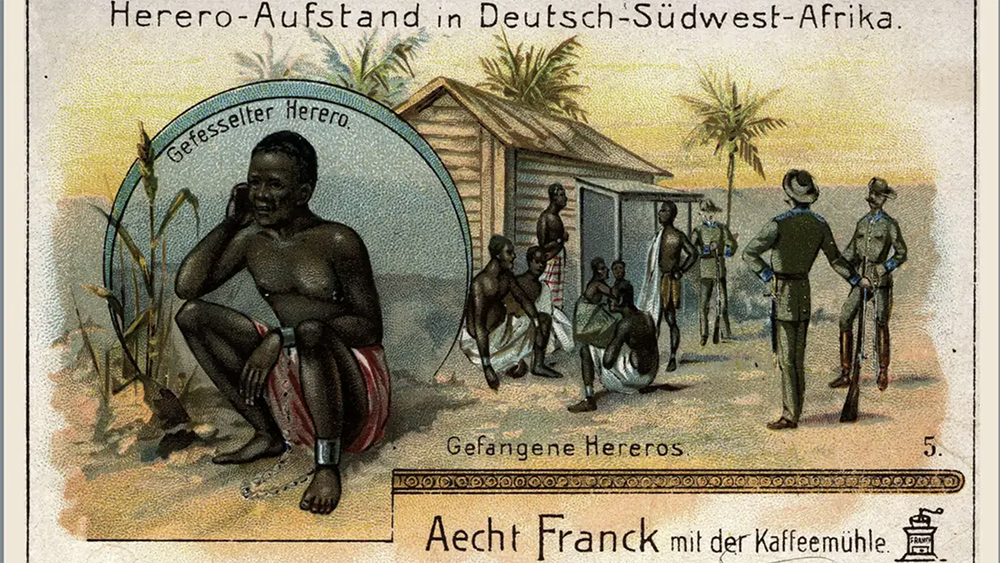

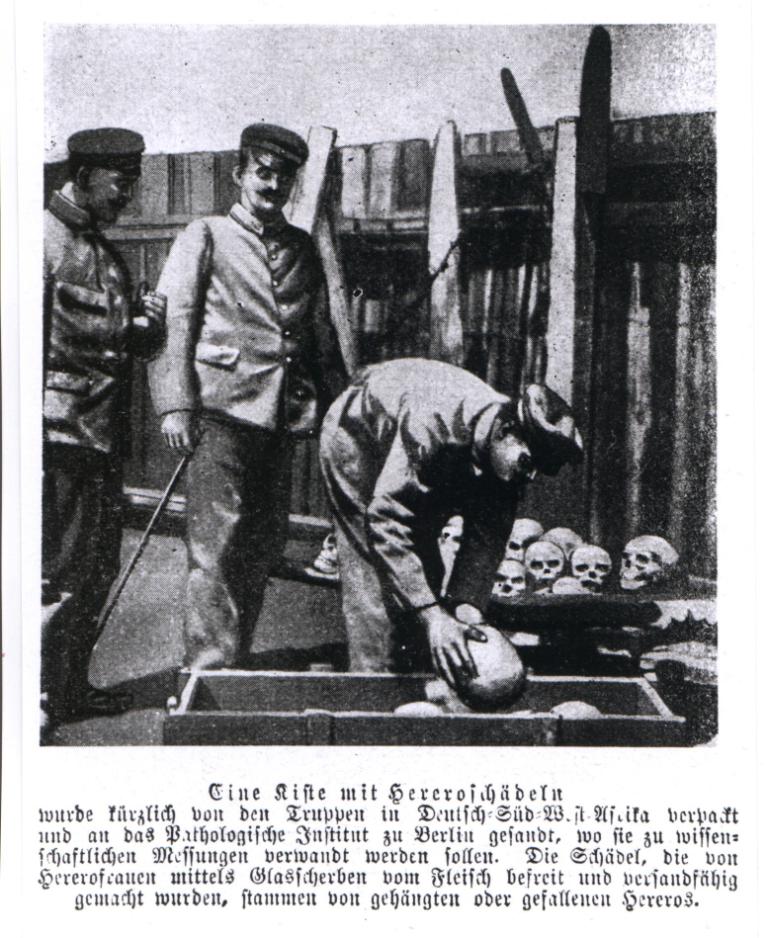

This set the tune for numerous subsequent “punitive expeditions” against indigenous people who resisted the German “protection”. As figures suggest, during the whole colonial period of 30 years, the number of Germans in the colonies at any given time remained – even at the peak periods when soldiers were deployed – less than 50,000. But far more than a million locals paid with their lives in the direct forms of warfare conducted in the territories. Corporal punishment and executions, sexual abuse and forced labour were the order of the day. The Nilpferdpeitsche (hippopotamus whip) was widely associated with German rule in the West African territories.

A scorched earth policy in East Africa and the genocide in South West Africa were just the tip of the iceberg of a “civilising mission”. The Jewish-Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term genocide, referred in his writings to the case of South West Africa as an early example. Hannah Arendt observed in The Origins of Totalitarianism, that German colonialism and an anthropology obsessed with Arian superiority were the cradle of a mindset, which culminated a few decades later in the Holocaust.

With World War 1 the German colonial empire collapsed. The Treaty of Versailles allocated in 1919 the territories as mandates to allied states, thereby partly redistributing the colonial cake. Perceived as humiliation, this did not bring an end to German colonial ambitions, but rather reinforced the desire and demands. Colonial propaganda flourished during the Weimar Republic. It took new turns during the Nazi regime, when eying Lebensraum [living space] as a colonial project shifted towards Eastern Europe.

Fighting colonial amnesia

While the summary above underlines the lasting impact of the colonial era, many in Germany still tend to downplay the thirty years of overseas empire as a negligible historical episode bordering on the harmless. For more than a century since the notorious Berlin Conference of 1884/85, marking Germany’s entry into the club of colonising states, this era largely remained a matter of colonial-apologetic romanticism. More recently, the legacies of German colonial rule – not least for Germany herself – have become a matter of growing interest. In December 2021, the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the Green Party (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen) and the Liberal Party (FDP) formed the government. Its coalition agreement declared under the heading “Colonial Legacy” the intent to reappraise German colonial history with special reference to the restitution of objects from colonial contexts. It also promised to develop a concept for a place for learning about and remembering colonialism. The coalition wanted to put an end to existing continuities with the colonial past and to initiate independent academic studies reappraising colonialism.

As my monograph documents, such solid, competent, and independent scholarly work reappraising German colonialism already exists almost in abundance. Literature on manyfold aspects of German colonialism has flourished since the late 1990s in both English and German by scholars of a variety of disciplines. One therefore wonders if this declared intention is a sign of ignorance and simply reflects the blinders of official policy and policymakers, thereby confirming the absence of any awareness of what is already known of this past.

What David Andress diagnosed for the UK, France, and the US as Cultural Dementia, applies to German colonial amnesia too: “the layering of mythology around history is not something that can be simply and uncontroversially pulled back by the application of expertise. The West’s current relationship to the past is … an actively constructed, jealously guarded toxic refusal to engage with facts that are well-known but emotionally and politically inconvenient.” Such “loss of memory” has been at the heart of national identity formation since the birth of the so-called nation-state. As Ernest Renan already observed in a lecture at the Sorbonne on 11 March 1882: “Forgetting, I would even say historical error, is an essential factor in the creation of a nation and it is for this reason that the progress of historical studies often poses a threat to nationality. Historical inquiry, in effect, throws light on the violent acts that have taken place at the origin of every political formation.”

But while dementia seems irreversible, colonial amnesia is not. Continued awareness campaigns have left their marks in the former empires. In Germany, there are noticeable signposts towards a “decolonial turn”. It has made inroads in the public sphere, whether this has to do with the bilateral German-Namibian negotiations over the genocide in South West Africa, the controversial Humboldt Forum or the restitution of human remains and looted cultural artefacts.

Relentless efforts by local postcolonial initiatives, including a growing role by Afro Germans, campaigning for the renaming of public spaces and questioning other forms of colonial memory, racism, and discrimination, have made inroads in everyday life. These, as well as the lines of defence by colonial apologetics, are documented in my book, which spans from the first German involvements in the slave trade until the current battles over the power of definition.

After all, amnesia does not mean that the topic of colonialism is or has been absent from the public sphere. Rather it means, that the dominant discourse ignores existing counter-knowledge or applies some degree of immunisation against its revelations. These are available as sources and can be accessed by anyone. Such knowledge, therefore, is not expunged from “storage memory” but rather kept away from “functional memory”, as Aleida Assmann pointed out in Cultural Memory and Western Civilization.

Summarising numerous critical explorations into the German colonial history and its lasting trajectories since then, disclosing amnesia, denialism, and revisionism in the current responses to postcolonial initiatives in scholarly and civil society spheres, The Long Shadow of German Colonialism presents further insights concerning the challenges, and contestations relating to the subject. It might be considered as an encouragement for post-colonial initiatives and scholarly work in Sweden too, to tackle the “forgotten” past of a Swedish involvement in efforts to exterminate all the brutes, for which the late Swedish scholar Sven Lindqvist set an example through his pioneering study.

Henning Melber

Henning Melber came to Namibia as a son of German immigrants in 1967. He joined the anticolonial movement SWAPO in 1974. In 2000 he moved as Research Director of the Nordic Africa Institute from Windhoek to Uppsala. From 2006 to 2012 he was Director of the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation. He remains associated to both institutions and is also Extraordinary Professor at the University of Pretoria and the University of the Free State in Bloemfontein and Senior Research Fellow with the Institute for Commonwealth Studies at the University of London.

Read also

|

Uppläsning av artikel

|