ANALYSIS. With fewer contractual steps and intermediaries, the Swedish government wants to achieve greater efficiency, less bureaucracy, better control and more resources reaching local organisations in partner countries. But why didn’t anyone think of it before, if it was so simple? asks Göran Holmqvist, former head of Sida’s Asia and Humanitarian Affairs department.

The opinions expressed in this article are those by the author.

Finally, after long waiting, the Swedish Government has issued a new strategy for development cooperation with civil society. One of its major changes is to limit the forwarding of funds:

”Forwarding of funds in more steps than one should, as a rule, be avoided. The agency [Sida] may grant well-reasoned exceptions.”

By limiting the forwarding of funds, the Government wants to achieve efficiency, less bureaucracy, better control and more resources reaching local organizations in the partner countries. It sounds great – why hasn’t anyone figured it out before if it was so simple?

Let us draw the parallel to the private business world and imagine that someone in a boardroom gets the flash of genius to bypass all the wholesalers – here is a potential to improve efficiency, get hold of the wholesalers’ profits and to establish direct contact with the end customers! Let’s assume that experienced board members then raise a number of objections: ”We lack the wholesalers’ network and local knowledge; The wholesalers have economies of scale in transport, storage and much else; If we were to set up expensive local offices everywhere then we become heavy-footed and inflexible; Wholesalers reduce our political risk in countries where we do not want to be too visible.” Perhaps someone would point out Amazon’s (and others’) successful model where you place yourself between several wholesalers. One can imagine that the discussion in the company’s board ends up in: ”The benefits of cutting out wholesalers could maybe be a good idea sometimes but hardly always, so let’s calculate the matter carefully and weigh the risks!”.

The government’s intention to cut out the intermediaries does not seem to have been characterized by the same thoughtfulness. Has the pros and cons been carefully assessed?

What can we learn from wholesalers?

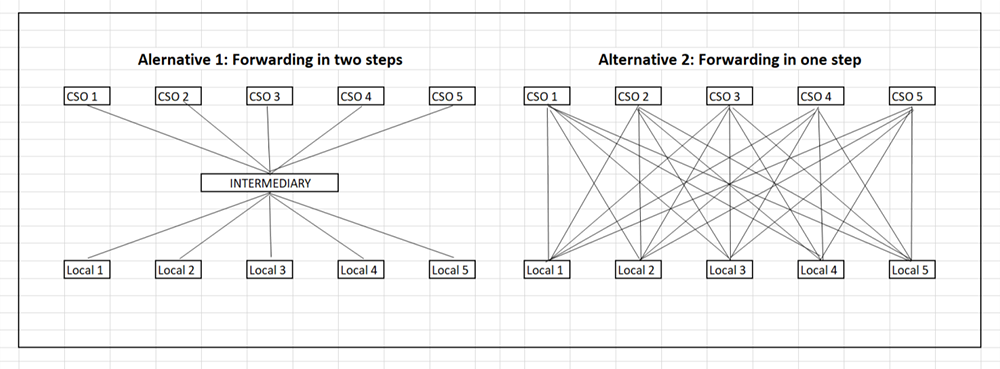

Just as the wholesalers can contribute to efficiency, so the aid industry’s ”wholesalers” – the intermediaries – can do so. The image above illustrates. Suppose there are five civil society organizations in northern countries that all want to support local gender advocacy organizations in an ODA country. No one wants to put all their eggs in one basket, or to favor only one actor, so they prefer to support several local organizations. Assume that there are five such local organizations that the organizations in the north all have identified. In alternative One in the picture, ”Forwarding in Two Steps”, the five civil society organizations choose to pass on the resources via an intermediary (hopefully with local knowledge, embedded in local networks and with economies of scale for administration and capacity support). Each local organization then only has one contractual relationship to manage, the one with the intermediary, and in total there will be five such contractual relationships for the local ones. If we now assume that the intermediary is excluded (forwarding in more steps than one is ”as a rule to be avoided”), we end up in a situation that is illustrated by alternative Two in the picture, ”Forwarding in One Step”. Each local organization then has five contracts to manage, and the total number of contract relationships becomes twenty-five! At the same time, the intermediary’s economies of scale are lost when administration and capacity support are divided among five different organizations. When we remove a contractual link, there are in fact five times more contractual relationships for the local organizations to deal with, and five times more for the civil society organizations in the north! It does not sound like a recipe for efficiency, reduced bureaucracy and better control.

It is well known that the aid landscape is often too fragmented, which affects local recipients with limited administrative capacity. The mechanisms for improved coordination have either been about division of labor (each one does its part, which works to some extent but in practice is often difficult as it requires coordination at the top of the steering chain) or about the pooling of resources via a common actor – an intermediary. Excluding a priori the latter administrative solution does not guarantee efficiency and reduced bureaucracy.

Increased localisation

Another ambition in the Swedish Government’s strategy is to increase localization; more support must reach the local level. However, it is extremely doubtful if this is achieved by limiting the forwarding of funds to a maximum of one step. The Swedish civil society organizations will have to establish contractual conditions with their partners that outrule their forwarding of funds. The risk is then obvious that the partner, often perhaps a centrally located NGO, is pushed into direct implementation, competing with the true local organizations in the field. The rule that forwarding of funds is to be limited to just one step, is in fact a strong incentive for direct implementation. That is, the opposite of localization.

The hope seems to be that Swedish embassies will handle the support to the small local organizations (a special window is specified in the strategy, which should grow over time). The question that is then raised is whether the Swedish embassies are efficient units for handling small contributions in small volumes, for which they lack economies of scale. The cost of a Swedish programme officer at an embassy is approximately SEK 3 million per year. Even if that program officer were to succeed in the art of handling, say, 10-20 local NGOs for 10 million SEK, then that implies and administrative overhead of at least 30%. Will it survive an efficiency audit by the Swedish Board of Auditors? Sometimes embassies certainly may have a role to support local civil society directly, but then it should be well reasoned, strategic and compatible with intergovernmental relations.

Perhaps the foremost example of achieving efficiency through intermediaries can be found in the humanitarian field (not affected by this strategy, but a new humanitarian strategy is expected in 2025) in the form of the UN’s humanitarian country pooled funds, to which Sweden is a major donor. With resources pooled from several donors, thousands of small local humanitarian organizations are reached, those with local presence that can make a difference. However, the contractual steps are frequently more than one. It is not conceivable that Sweden could achieve such economy of scale on its own. Being able to flexibly reach those organizations furthest away can be a matter of life and death in humanitarian operations.

Where is the added value?

Of course, all this does not mean that occasionally there may be good reasons to cut out intermediaries, when their added value does not correspond to the cost. One of the perverse incentives that exist in the aid industry is generated by the fact that many actors are subject to administrative restrictions – you have a binding restriction in the internal administration budget but not for the administration that takes place in subsequent contractual steps. By forwarding funding, some administration can be further delegated without it appearing in the organization’s account of administrative costs. So, there is a risk that money is sent back and forth in an inefficient way. But the solution to that problem is not an inflexible rule where the steps of forwarding of funds are counted, but that you demand that the added value of each contractual step in the chain be weighed against the costs. How this weighing is to be done can be clarified in the procedures of an organization such as Sida.

Fortunately, the government has now written in the strategy that Sida may grant well-motivated exceptions. Let’s hope for Sida’s wise application of that opening. But since the Government does not make any reasoning about what well-motivated exceptions are, which it should have done, the risk is great that that Sida err on the safe side and goes with the clear but inflexible principle of no forwarding of funds in more than one step. That is to say that in many cases intermediaries will be cut out without further consideration, and we end up in the messy Alternative 2 of the picture above.

Göran Holmqvist

Göran Holmqvist has more than 20 years of experience in management positions in development cooperation. Over the years Göran Holmqvist had led Sida´s operational departments in all developing regions of the world. In 2024, he resigned as head of Sida’s Asia and Humanitarian Affairs department.

A Swedish version of this article has previously been published. You can find it here.

Read also

|

Uppläsning av artikel

|