In a country where certain combinations of colours are banned fashion can be a tool to resist the authoritarian regime and an act to preserve our Belarusian national heritage for the future, writes artist and curator Ludmila Christeseva.

Recent incidents in Belarus, such as the authorities’ scrutiny during an artistic presentation at a café resulting in a 15-day detainment, weigh heavily on every attempt to collaborate with Belarusian artists. The waiting time for replies from colleagues fills with concerns about their safety. Any collaborations are overshadowed by conspiracy and prayers: ”Hope they are okay!”.

A fashion student’s thesis defence was thwarted due to her daring interpretation of the Belarusian national colours, white, and red. The precarious balance between her freedom and constraint prevents us from disclosing her name. The realization of her vulnerability leaves us pondering: will her identity ever be revealed? The imposition of a forbidden dress code raises profound questions: What role does culture play? How do we preserve our national identity and cultural heritage through fashion and the arts? Beyond historical narratives and traditional motifs, what symbols, colours, and designs might encapsulate the essence of Belarusian heritage for future generations?

The projects initiated before the conflict in Ukraine did not anticipate the ensuing complexities of war as a main risk. This turned several curatorial goals, ranging from artist residencies and networking with international curators to planning exhibitions, recording podcasts, and crafting books chronicling the remarkable women of Belarusian history, into a distant dream.

Additionally, it erased even the colours blue and yellow, symbolizing solidarity with Ukraine, from the palette of the Belarusian artists. The use of these colours can inadvertently attract unwanted attention and put individuals at risk. This highlights the need for a decolonized approach to cultural expression, where artists reclaim symbols and colours from the grip of oppressive regimes. So what colours are left in the palette of the Belarusian contemporary artist?

Today we learn the names of Belarusian activists, artists, and designers through newspaper headlines detailing their trials and the loss of their freedom. How many of these creative souls will withstand the suffocating censorship of repression? This issue has gained widespread international attention, notably due to the involvement of prominent Belarusian human rights defender and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Ales Bialiatski (2022), who has advocated for political prisoners in Belarus and called for the release of all political detainees.

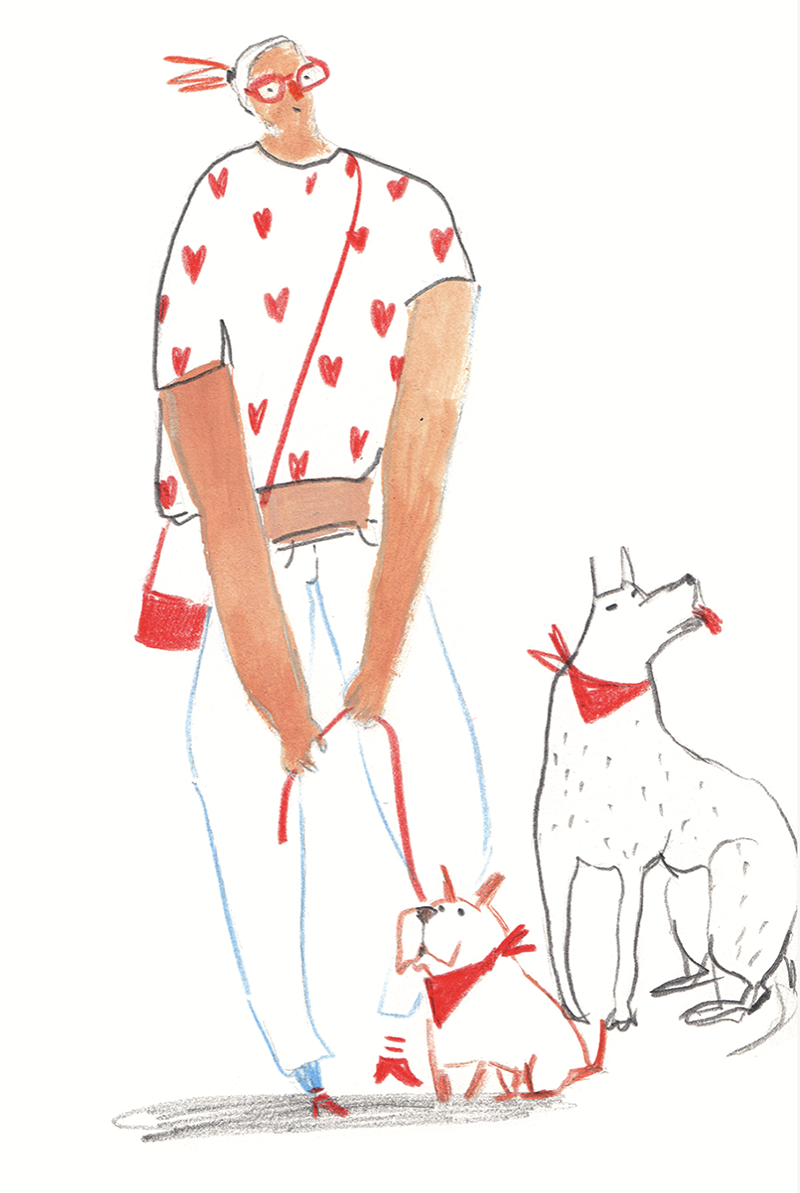

The pressing question arises: How can we effectively amplify the visibility of Belarusian artists while ensuring their safety and anonymity in the midst of an authoritarian political climate? In pursuit of an answer, I turned to AI to explore the theme of artistic evolution within contemporary Belarus. Given the potential risks associated with activism through art in Belarus, artists should approach this strategy with caution. For every expression in Belarus, people face repression. Even the simple act of wearing white and red colours and designs is a forbidden dress code. For instance, in 2020, a young Belarusian student named Andrey Krylov was sentenced to 13 days of arrest for wearing a white T-shirt with red stripes, as well as for spreading opposition symbols on social media.

AI suggests that group exhibitions could offer a viable solution by redirecting the focus onto the artwork itself rather than individual artists. This approach enables artists to actively engage in art production, share knowledge, and sustain their presence in the profession. By collectively showcasing their work, artists can underscore the significance of solidarity in mitigating the risk of exposure.

This collaborative approach empowers artists to exhibit their work without compromising their identities to the public eye. While anonymity remains a potential solution, it raises the question: How can an artist inscribe their name into art history without revealing their identity?

International solidarity is paramount, as emphasized by AI. Collaboration is essential for Belarusian artists facing repression, and access to artist residencies abroad is crucial. Each interaction with international colleagues provides an opportunity to amplify their voices and advocate for change on the global stage. Our support is vital for the resilience of the artistic community and its capacity to adapt and evolve in response to changing circumstances.

In closing, any collaborations with Belarusian artists stand as a testament to the resilience and creativity of Belarusian artists in the face of adversity. As we navigate the complexities of an authoritarian political climate, it is imperative that we continue to amplify their voices, advocate for their safety, and provide platforms for their artistic expression. How can we further empower these artists to resist and persevere? What role can international solidarity play in shaping the future of Belarusian art? These questions compel me to reflect on my own responsibility as a curator and as a native of Belarus, engaging the global community in the preservation of Belarusian heritage for future generations.

Ludmila Christeseva

Background

May 21 is designated as a day in support of political prisoners in Belarus, and the urge to dress in these colours tends to be a significant trend among Belarusians who have fled the country. This movement underscores the power of fashion as a tool to resist the suppression of the authoritarian regime and as a collective act to preserve Belarusian national heritage for the future.

18.30 on the 21st of May there will be a manifestation for Belarus.

On the same day Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya will be Stockholm to participate in The Stockholm Conference on Belarus 2024, organized by the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs in cooperation with the Stockholm Centre for Eastern European Studies (SCEEUS) at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs (UI), on May 21-22, 2024.

Note: The flag was created by several persons as part of a manifestation 2020, with Ludmila Christeseva being one of them. The flag was also part of a performance, created by Edvard Tarletski.

Read also

|

Uppläsning av artikel

|