Khartoum has always been a hub of creativity. The destruction of my home town has caused me to reflect on its construction. What is being lost is much more than just buildings. It is also people’s hope for a future they had invested heavily in, writes Amira Osman, a scholar of Sudanese architecture.

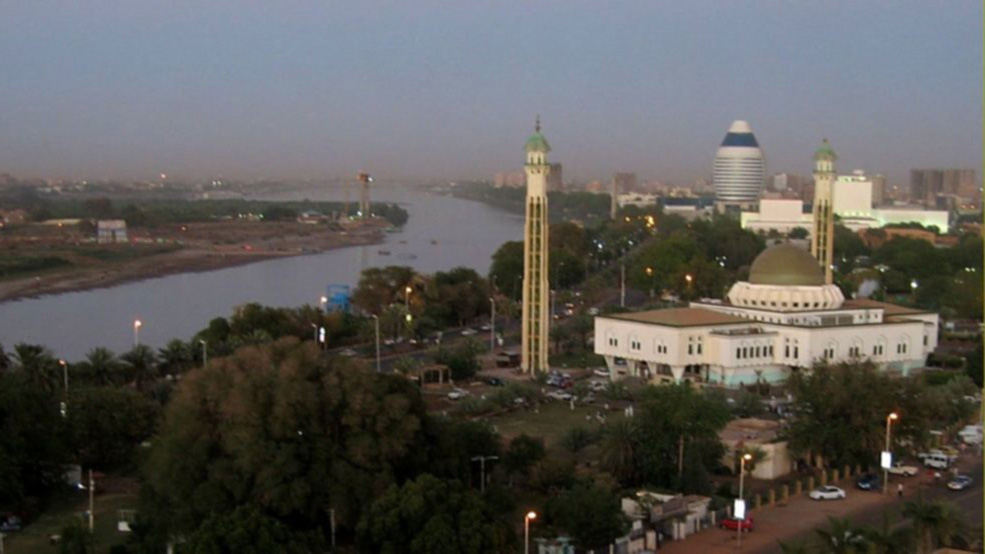

Khartoum is – was – a city that did not know war or fighting in its recent history. Now it is in the grip of a civil war between rival military forces. The city has always been a hub of creativity. It was awarded the title of Arab Capital of Culture in 2005. Despite its Arab affiliation, the capital of Sudan is also very African. A tension of identities – British colonial, African, Islamic – made Khartoum what it was.

This triple heritage is powerfully reflected in Greater Khartoum’s composition as three towns separated by rivers with a network of bridges. Omdurman is considered a national capital, the symbol of the values of the people, while Khartoum is the administrative capital and Bahri (or Khartoum North) is the industrial town. Together, they are simply known as Khartoum.

A narrow part of the city, about 20 km across, between the Blue and White Nile rivers, is where the airport and military headquarters are located. Around them are dense residential neighbourhoods. People have had to evacuate their homes as this narrow strip was one of the first invaded. The rest of Khartoum is now equally destroyed at a massive scale.

I’m a scholar of Sudanese architecture who was born and raised in Khartoum by an architect father. The destruction of my home town has caused me to reflect on its construction. What is being lost is much more than just buildings. It is also people’s hope for a future they had invested heavily in.

City of hope

Like many African cities, Khartoum is divided into pockets of wealth and poverty. Over the past century it has expanded significantly.

The city has unique geographical features that could also have become opportunities for future development. The most significant are al mughran (the confluence), a meeting point of the two River Niles and Tuti Island. They offer many river fronts, presenting great prospects for residents. Formal and informal businesses thrived along the rivers, as did cultural and entertainment opportunities.

This created innovations such as open air book fairs and art markets, as well as more formal and well-funded initiatives, which sometimes led to tensions over conflicting interests. Khartoum could have been conceptualised as a city of hope and opportunity.

In a 2003 study on safety and crime in various African cities, the conclusions on Khartoum mention religion as a deterrent for criminal activities. Greater Khartoum had a low crime rate in comparison with other major cities in the world.

Despite a dictatorship and a people’s uprising, Sudan was safer than visitors expected.

“Even its military coups were lethargic and bloodless,” wrote one Sudanese journalist, citing Khartoum as a selfish city for remaining peaceful despite a country burning around it. Perhaps the city, located in the centre of the Sudan, never really stood a chance for lasting peace with its tumultuous peripheries.

This city is now a ghost town of abandoned homes, snipers and dead bodies on the streets. The militia are occupying most of it, rendering residents human shields as the army attacks them from the air.

Changing landscape

In the late 1980s and 1990s, many educated Sudanese left the country due to political instability, high unemployment rates and the general difficulty of day-to-day life. Yet, like many Africans in the diaspora, they never lost contact with the home country.

During this time, building guidelines changed and Khartoum densified. Plots that previously had a single-storey family home now became three- or four-storey apartment blocks, and the city expanded vertically. Property dynamics adapted to receive the newcomers – as well as the massive cash injections from Sudanese abroad. One migration profile states that in 2013, US$424 million was sent back to Sudan – 0.65 percent of its gross domestic product.

Much of this funding was used to develop properties in Khartoum, either for rental, for family use, or for those abroad when they returned for annual visits or in anticipation of their ultimate retirement. In a country with broken systems and institutions and little opportunity for other forms of investment, Sudanese invested heavily on their homes. In Khartoum, rental income is – was – the only form of retirement funding for many citizens.

The Sudanese social and political context during the formation of the country’s modern movement in architecture from 1900 to 1970 influenced the development of Khartoum’s architecture in profound ways. It led to a unique architectural identity. What emerged was a form of architecture that adapted to the climatic conditions, as well as the sociocultural needs of the people. Bands of reinforced concrete, deep verandahs, large balconies and panels of face brick came to characterise many homes in the city. As time went on, these homes became multiple-storey, mixed-function developments.

One Sudanese architect, Omer Siddig, played a part in developing the architectural identity of the city. He is also my father, with whom I trained with for many years and who is completing a book on his archives, mostly of buildings in Khartoum. In this archive he explains how a unique form of residential development emerged as his company spent more than 20 years providing building solutions for dynamic family needs:

The model that evolved was adopted and replicated widely; it allowed for the family to occupy the ground floor section while the upper levels comprised apartments for use by the children of the family as they married. This system replicated the model of homes of extended families in the rural areas from where most of Khartoum’s residents originated … This allowed the houses to incorporate rentals on the upper levels without compromising the privacy of the main home.

The loss

So as the city continues to be destroyed, one must also wonder about the loss of everything that people have acquired over their lifetimes and what the consequences will be.

Leaving Khartoum means leaving behind assets, income-generating opportunities, access to education and healthcare. Leaving Khartoum means a humanitarian crisis of great magnitude that will affect not only the rest of Sudan but the whole region as over six million people lose everything they ever had.

A war in Khartoum means not only the displacement of people and the destruction of buildings and infrastructure, but also the loss of a rich heritage. People have lost lives, livelihoods, communities, unique innovations, their sense of place, belonging and identity, and the refuge that the city offered. It means the loss of hope in a dream of what could have been.

Amira Osman

Professor of Architecture and SARChI: DST/NRF/SACN Research Chair in Spatial Transformation (Positive Change in the Built Environment) at Tshwane University of Technology.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.