On March 17 2023 the ICC issued its first arrest warrant against Vladimir Putin. But much less has been said about the charges brought against Maria Lvova-Belova, the Russian Commissioner for Children’s Rights. Lvova-Belova’s situation is rare in international criminal law. She is only the second woman against whom charges have been brought by the ICC, writes Caleb Wheeler from Cardiff University.

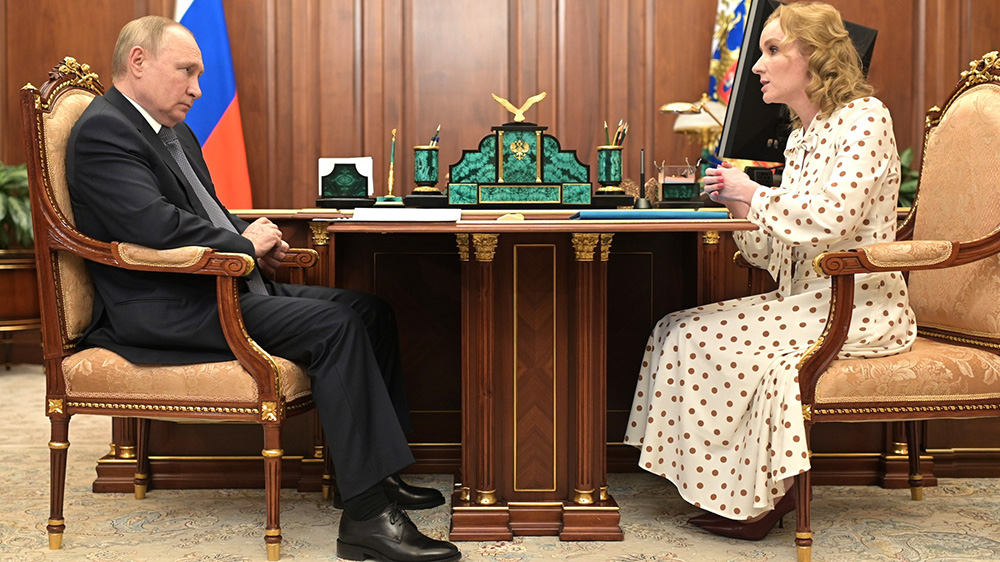

Within days of the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the International Criminal Court (ICC) opened an investigation into war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during the resulting war. On March 17 2023, the ICC issued its first arrest warrants against two Russian government officials. While significant attention has rightfully been paid to the arrest warrant for the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, much less has been said about the charges brought against Maria Lvova-Belova, the commissioner for children’s rights.

The ICC alleges that Lvova-Belova engaged in two different war crimes described in Article 8 of the court’s statute. Both relate to the unlawful deportation or transfer of the civilian population of an occupied country.

The warrants are based on the theory that Lvova-Belova, either acting individually or as part of a plan, removed orphans from Ukraine and deported them to Russia, where they have been adopted by Russian families. It has also been reported (although not specifically stated in the warrants) that Ukrainian children have been sent to reeducation camps in Russia for the purpose of promoting cultural, historical, societal and patriotic messages or ideas that serve Russian political interests.

Lvova-Belova’s situation is rare in international criminal law. She is only the second woman against whom charges have been brought by the ICC, and the sixth female suspect at any international criminal justice institution. In contrast, women are often the victims of international crimes – rape and other forms of violence against women occur frequently during armed conflicts. Despite this, prosecutions for these crimes have proved difficult. The ICC often prosecutes for rape and other crimes of sexual violence, but it has only secured two convictions for those crimes.

There is no clear explanation about why women have so rarely been the subject of international criminal prosecutions. It is not that women do not commit international crimes – many have been convicted in national courts for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during the second world war, the Rwandan genocide and the war in the former Yugoslavia.

One reason women are not often prosecuted by international criminal courts and tribunals could relate to the small number serving in senior leadership positions in many countries. While it is not unheard of for the ICC to prosecute more junior officials, their approach has largely been to pursue more senior government and military officials.

In Russia, women occupy fewer than 10% of senior leadership positions in the government and the military. Of the 31 senior leadership positions in the Russian government, only three are women. There are also only three women among the 35 people identified as major staff and key officials in Putin’s executive office.

Women are even more underrepresented in Russian military leadership. One of 13 senior Russian military leaders is a woman. Simply put, women in Russia may be committing crimes that are of interest to the ICC, but lack the seniority to be considered among those who bear the greatest criminal responsibility.

When women commit war crimes

On the rare occasions that women are pursued by international criminal courts and tribunals, gendered stereotypes are often employed in an effort to justify or excuse their criminal behaviour. Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, Rwanda’s minister for family welfare and the advancement of women, was charged in 1999 by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda for her involvement in the 1994 genocide.

In an interview with the BBC, she denied playing a role in the crimes, asserting that as a mother she could not have been responsible for killing another person. One of her lawyers later emphasised her protective maternal instincts by describing her as “a mother hen”. Despite this, Nyiramasuhuko was ultimately convicted in 2011 of seven charges, including genocide and incitement to commit rape.

Similarly, Biljana Plavšić, the former president of Srpska (a territorial entity within Bosnia and Herzegovina) was the only woman prosecuted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. She has been characterised in the media along gendered lines, alternatively being described as “the Iron Lady of the Balkans” and “the Ice Queen”.

Plavšić’s defence to the charges against her were constructed around the idea that she was acting as “the mother” of her country, and that her behaviour was justified because she was protecting “her family”, the Serbian people. Plavšić ultimately pleaded guilty to the crime against humanity of persecution and served two-thirds of an 11-year sentence. But she later repudiated her plea, insisting that she had done nothing wrong.

These sorts of gendered narratives have also sprung up around Lvova-Belova. It has been reported that at times the Russian media has referred to her as “Mother Russia”. She has described herself as the saviour of Russian children, helping to shield them from the violence of war.

She also adopted one of the children transported from the occupied portion of the Donbas region in Ukraine. She uses that adoption to suggest that she understands what it means to be the mother of a deported child.

Taken together, this paints a picture of someone justifying their actions on the basis of their role as a mother, while simultaneously downplaying the political dimensions of their behaviour. Should this case ever come to trial, it is reasonable to surmise that a similar strategy will be deployed in her defence. As a result, it is crucial for the ICC to ensure that the case against her is evaluated on its merits, and not a constructed gender identity.

Caleb Wheeler

Lecturer in Law, Cardiff University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.

Read also

|

Uppläsning av artikel

|