The city of Belgrade is far from handsome and neat. Le Corbusier supposedly said that Belgrade is the ugliest city in the most beautiful spot and that’s not far away from the truth. The city is full of scars and wounds. It’s beautiful the way Keith Richards is. Loving it is a matter of choice, writes Predrag Dragosavac in this essay about Belgrade, once the capital of a country known as Yugoslavia.

Like many other people in Belgrade, my friend Pedja, a tourist agent who founded a nice and useful site about the city, fights against everyday frustrations with cynicism. ”It’s a pity that I’m not a Croat or Slovenian… to be cheerful and excited about a weekend in Belgrade”, is one of his witty jests around the fact that Croats and Slovenes are the most numerous ”foreign” visitors of Belgrade. Pedja’s jest epitomizes the heart of the matter by killing two birds with one stone. Belgrade is not an easy place. It’s rather hard. It’s the hardest for its’ own citizens. Still, it is a real city, a really big city, the only such a city – real and big – in the space previously known as Yugoslavia.

My dwelling place in the last several years has been Stockholm. I’ve changed three addresses in it and got to know the city both from the over-hyped and very Swedish ”Southern island” – Södermalm, as well as from the dominantly immigrant ”suburb” Bredäng. Those are very different realities. But, all in all, when compared with Belgrade, Stockholm is calmer, cleaner, better organized; the air is better, traffic and transportation go smoother, the living standard is significantly higher…

Still, when it comes to socializing, going out or taking it easy, Belgrade is more thrilling. There you meet people all the time, it’s not necessary to plan it weeks ahead; venues can run the whole night; there are no uniformed guards to annoy at the entrance of every single bar… I’m also cheerful and excited about weekends in Belgrade. But, I don’t like Mondays… and sobering up in the Serbian reality. Headache is inevitable even if you aren’t drinking at all.

Still, at this stage of my life, I can claim that Belgrade will always remain more ”mine” than any other city, no matter where I go and stay from now on. There I grew up and spent most of my life, there my parents and most of my friends live, there are people on the street who recognize me and I recognize and meet someone all the time…

Belgrade is far from handsome and neat. Le Corbusier supposedly said that Belgrade is the ugliest city in the most beautiful spot. That’s not far away from the truth. The city is full of scars and wounds. It’s beautiful the way Keith Richards is. Loving it is a matter of choice. I do love it, despite everything. In the same time, I have a huge problem with it. There are too many things there, and too many people, that I’m sick and tired of…

Change of Soundtrack

At one point of my ”exile”, I was repeatedly having a pretty nightmarish dream: I’m walking through Belgrade and not recognizing anything, not meeting anyone familiar… I woke up disturbed. What was that? It wasn’t necessary to be Freud to rationalize: it must be about (e)migrating, ageing, losing touch, about detachment and alienation.

Contemplating retrospectively about my detachment, I know now that it didn’t come overnight. However, I wasn’t aware of it for quite some time. Or maybe I was just pissing against the wind, refusing to acknowledge something obvious. Whatever way, sobering did shock me.

In the early 2000’s I had regular talks with my late friend Laza, who was an extra-ordinary character – poet, writer, translator, guitar player, living encyclopaedia… He was writing for the pop-culture page I was editor of, and as my newspaper was literally next to the building he was living in we were often having ”cups of talk” in the neighbourhood.

We were often elaborating ”the sound of Belgrade”; how the music, bands, venues… in the city had been changing and what had remained of the once colourful scene. One of our basic premises was that Yugoslav rock’n’roll scene was authentic in a similar way as Yugoslav basketball – the seed was brought from elsewhere, but through the time an authentic and distinctive ”plant” was grown.

The golden time was late 70’s and the first half of the ’80s: a bunch of bands – post-punk, new wave, electro, and all kinds of others from disco to symphony and glam rock bloomed as mushrooms after rain. For the moment the feeling was that Belgrade was the centre of the world – exciting, adventurous, ”smelling of sex”, as David Byrne would say for New York.

Just a decade, decade and a half later, most of that scene vanished. Many Just a decade, decade and a half later, most of that scene vanished. Many people left the country, some stayed and experienced complete marginalization, some conformed to the dominant madness. Many also died, or rotted, from heroin. In Belgrade, heroin was ”acting” very high – it was mowing young arty and intellectual crowd as a plague in the Middle Ages.

Koja, one of the main figures of Belgrade’s underground and spiritus movens of two cult bands Šarlo akrobata and Disciplina kičme, had spent that decade in London. But, he was keeping in touch and trying to re-connect with the city.

”It seems to me that Koja, after so much time spent in London, alienated from Belgrade”, Laza was saying in one of those conversations of ours. ”Maybe Belgrade alienated from itself”, I replied spontaneously. That was the first time I verbalized that thought. That’s why I remember it.

In the similar time, I’ve met for the first time another hero of my childhood, Vlada Divljan, from the band Idoli. While Koja was always nurturing the image of an awkward and grumpy underground figure, Divljan was very much on the opposite side – handsome, polite, pleasant, intellectual, and sophisticated… I would say that both Divljan and Idoli were an emanation of the most sophisticated Belgrade, probably ever.

We were doing an interview on the abandoned roof of the building in the centre, where the office of my newspaper was located. I would say that we became friends in no time. At one point, he took out a bottle of whiskey from his bag – ”I’ve prepared for the rehearsal with the band, I go there afterwards”, we rolled a joint…and the talk lasted for hours, much less for the interview, much more for our own sake.

Divljan left Belgrade in the end of eighties, to Australia, and later on, moved to Vienna. We talked then, as several times later, about ”paradox” of migration – he felt well adjusted to new living environments and claiming ”not fitting into the Serbian prose”, mocking basically dominant mind-sets of Serbian pseudo-elite. That was the title of the interview: ”I’m not fitting into the Serbian prose”. The photo was from the roof – Divljan and Belgrade behind him. In the same interview, he was claiming how there’s no other place on the earth where he can communicate and ”click” with people so easily as in Belgrade.

In that time I didn’t bode that 10, 15 years later I would feel practically the same. I still didn’t question the relationship between Belgrade and me. I felt it as an unconditional bond ”for good”. I was well aware of the city’s deterioration during the long agony of the nineties, but I felt it as temporary. I somehow expected that river would come back to its’ riverbed when storms calm down. Even in the hardest and ugliest times of that hard and ugly decade, I was happy to come back to Belgrade wherever I was going.

Leaving was out of the question. I happened to be in New York, and later in Budapest, while the NATO bombing of Serbia and Belgrade was taking place, in 1999; I came back as soon as the state of emergency was lifted. Many people were looking at me, then, as I was some kind of lunatic. But, I lived on demonstrations, and for demonstrations, for the whole decade. I wanted to see ”the end”.

I wasn’t so naive to believe that the ”democratic change”, which occurred in Serbia in 2000, would bring overnight improvements. I did believe though that it would have some positive offsprings. Even in the worst nightmares, I didn’t expect that ”democratic change” would prove to be nothing more than an awful, disgusting lie; a great swindle with no rock’n’roll.

The frame of new ”freedom” very quickly got the Orwellian shape. Newspeak became new ”alphabet”. According to it democracy means colonization; progress means legal disempowerment of individuals; free market economy means ravishment of massive scale; freedom means submission; elite means thieves, criminals, war criminals and (inter)national scumbags of all kinds …

I was neither able nor willing to adjust to such a frame of life. That’s how the crack appeared. It was becoming wider and wider with the passing of time. I became maladjusted for the environment in which I had been living most of my life. It became easier for me to be anywhere else than there. Because, when being maladjusted seems like destiny, then it’s easier to be maladjusted somewhere else than ”at home”.

Poisoned and unpoisoned memory

The memory of the people from the space previously known as Yugoslavia who are old enough to remember the country with that name, in one piece, and ugly wars that over-killed it, have been poisoned. They became incapable to ”remember” how it was without incorporating what came later. As a consequence, there was a tendency either to uncritically romanticize the past or to uncritically negate it. Or, to block it completely.

I will, therefore, rely here on a memory of an ”outsider”. Who is, actually, a unique insider. Jody is more than just a high school friend of mine. We know each other from Jody’s hometown – Hendersonville, North Carolina. I was an exchange student there in the school year when the Berlin wall fell and everybody in the United States was so overexcited about it.

Jody was keen to come to Europe; I pursued him that Belgrade and Yugoslavia were the best places in the universe. He came in July 1990. As I had to ”pay the debt to the homeland” by serving the compulsory army service in the Yugoslav People’s Army, he basically replaced me in my room. The following nine months he would spend with my family, becoming a unique witness of history taking place.

At a certain point in the ’90s, when Yugoslavia became a synonym for trouble in a similar way as Syria is today, my contact with Jody was lost. On one hand, Belgrade was very much cut off; on the other, he literally disappeared. That was a disappointment, in many ways. From the perspective of the nightmare we were living in, it was hard to assume that somebody far away in the USA could go through awful situations as well, but that was a wrong assumption.

Anyway, it was Jody that discovered me after digging on the Internet. We finally met ”25 years later” in New York. He has been living there for years, working as a wine director in a fancy restaurant. Encountering anyone after a quarter of a century is a weird experience per se. This was even weirder. Jody is not anyone; he knows my family as an insider, as nobody else, basically.

To our encounter, Jody came with photo-albums. I was supposed to tell the stories about people on photographs. It was like a time machine. Many photos were from Karbuni, a small place on the island of Korčula, which is still kind of mythic for my family.

”That summer 1990 was the last time when everybody was there. Afterwards, it became impossible. Uncle Rade died during the 1990’s, out of sadness, I would say. Aunt Anita sold the house. The point was to have it as a meeting point for the whole family, for joy, and that became unimaginable. Family dispersed. Dragan left to Brazil to avoid going to the army; he is a helicopter pilot in Sao Paulo now, having two sons. Anita also went to Brazil when she retired. Nevena studied fine arts in Utrecht, Amsterdam and Granada and has been living in Barcelona in the last 7-8 years. Mom and dad are in Belgrade…”

All the stories told that day in New York were starting from the common history, i.e. from the very peculiar moment in our personal past – the intermezzo between finishing school and starting ”adult life”. We were American graduates – pretty careless ”shiny happy people”, certain about the bright future awaiting us.

As Jody left Belgrade while I was still in the army, we never really had a chance to talk about what came next. A quarter of a century later I was surprised about his ”lines” in the dialogue. I was stunned by the family tragedy he went through soon after returning to the US. I was also surprised by his extremely enthusiastic and positive view of Belgrade. He was calling it a unique urban experience that changed his life and gave him a cosmopolitan perspective.

”My heart is warm thinking of the time I spent in Belgrade, but I’m also left with a sense of longing – for that feeling of just being there at that time. And of being young, and being alive.” Ok, that maybe sounds expected. But, I was struck by Jody’s ”frozen memory”.

”Looking down from the bedroom window 15 floors: graffiti at the bus stop on the concrete slab below, dark streets with smoky restaurants, exhaust fumes, tramways, kiosks with open porno magazines, grand boulevards, statues and more statues. Staying out all night in ”Academia”. Goth girls and mod guys dancing to the Cult, the Kinks, the Cure, the Clash… Bridges, forts, street-front art galleries on the Knez Mihailova. Newspapers, bookstores, Gypsy bands, Militia leaders, academics, fashion parade… Concrete and stone, red yugos… Families living several generations together… Steam, smoke, cigarettes, BIP, hotel Moskva… Telling fortunes in coffee cups, drinking til’ dawn. Sarma, kajmak, rakia. Military tanks. Book stores. Open-air films in Kalemegdan. Friends. Art. Streetlife. Black grit from the street. Fountains. Cafes. Hotels. Miles Davis Live in Concert. ”

Jody’s reminiscences are the snapshot of the eve of ”big bang”: Goth girls and mod guys were to dance, militia leaders were for a different kind of party, tanks were already there, warming up…

Historical hints, myths and narratives

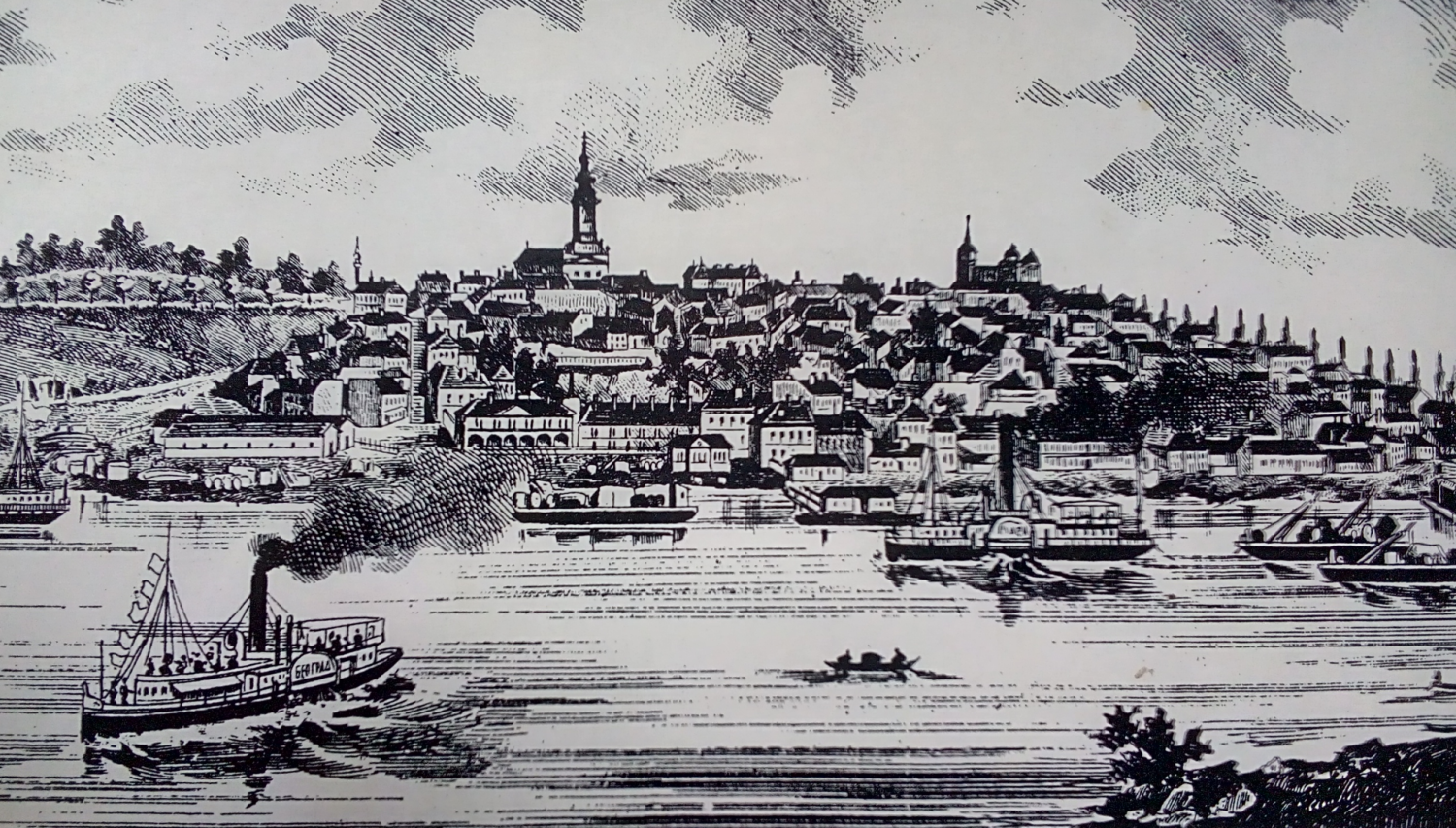

As countless other cities Belgrade also has that narrative about its ”important past”, official propaganda of greatness and uniqueness. ”White City. On the confluence of Sava and Danube. On the crossroad of civilizations. In the centre of the universe. Irresistible. Unconquerable. Destroyed many times. Always rising again from the ashes. Like a phoenix…”

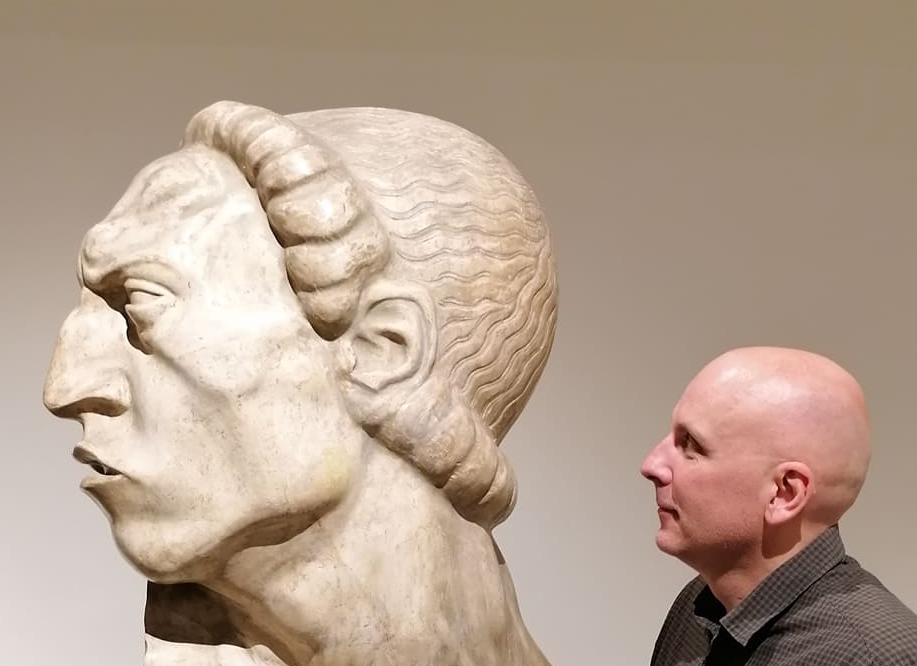

Probably the greatest myth about Belgrade is the one about the continuity, that all those burnt and demolished settlements in that spot represent one and the same Belgrade. That it’s ”spirit” survived all demolitions and historical U-turns. Would something like that be possible?

Whether perceived as one, same town, or as many towns in the same spot, even short ride through the history of Belgrade can’t be so short. Some historical hints are, however, a sine qua non for comprehending its story. As a house on the road, anybody doing business ’in the hood’ has been passing by and staying on there, staying overnight or longer, depending on their business plan.

From the early days, there was a fluctuation of people and peoples. The border on which Belgrade was leaning was often sliding. The city belonged for some time to the empire from one side of the river; other times it belonged to the empire on the opposite riverbank. That detail also determined its’ character. My belief is that people there had learnt, from cumulated experience, that all empires are transient, regardless of how great and powerful they might be at a certain point in history.

Despite the long history, Belgrade as a big city is the offspring of 19th century’s ideas, visions and aspirations. Like many others in Europe of that time, South Slavs, i.e. Yugoslavs, were striving for liberation, self-determination and unification. Empires they were living in –Ottoman and Habsburg – were declining. Common South Slavic state seemed as an aim worth of struggle.

Serbia was the first one from that South Slavic crowd to gain independence, as a result of the Berlin Congress in 1878. That was the official take off. Intensive Europeanization of Belgrade would take place. Alas, it was so ”intensive” that very few architectural testimonies of Orient and the Ottoman Empire survived. Kalemegdan Fortress, over the confluence of Sava and Danube, is standing. Turks were calling the place ’fecir bajir’ – the hill for meditation.

Besides being the Serbian capital, Belgrade evolved into a sort of South Slavic Piemont. Dozens of artists – poets, writers, painters from South Slavic lands were coming to find inspiration, as well as refuge and a safe haven. The great Croatian poet Antun Gustav Matoš (1873 – 1914) was one among many others celebrating Belgrade’s ”light” – literal and metaphorical one.

Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which later changed the name into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, was finally founded in 1918, as an outcome of the First World War. Instead of being capital of the state of 4 million people, Belgrade became capital of the complex country of more than 12 million people. That was certainly one of the major breakthroughs in its’ recent story.

Besides new shape and content of ”extended” state, there were some other important intellectual influences shaping Belgrade spaciously and spiritually in that period between the two world wars. One was ”French connection”. As France was Serbia’s main ally in the First World War lot of kids and ex-soldiers studied there. They were bringing ideas and fashions from Paris, the capital of the world of that era. That’s, for instance, how surrealism arrived, almost instantly, to Belgrade. In the same time, there was a ”Russian connection” as well; many Russian intellectuals who escaped the Bolshevik revolution ended up in Belgrade. They also gave enormous contribution in transforming a small provincial Balkan town into a European capital.

The German bombing of Belgrade on April 6, 1941, marked the beginning of Second World War in Yugoslavia. It was a brutal punishment for big Belgrade’s anti-Hitler demonstrations and the military coup d’état that suspended Yugoslavia’s pact with Axis. Main paroles on demonstrations were: ”Better war than pact!” and ”Better grave than slave!” Hitler fulfilled demonstrator’s ”wish” by sending 500 planes on Belgrade that killed more than 2,000 people in a day. Some of the nicest buildings in the city were demolished then, including The National Library.

An interesting and paradigmatic Second World War detail is that the largest destruction and devastation of Belgrade wasn’t caused by Nazis, but by the Allied forces. They undertook eleven separate bombing raids. There’s a cynical jest from that time which remains today: ”With such great allies and friends, one doesn’t need enemies.” By November 1944, nearly half of Belgrade’s buildings – 12,889 out of 30,000 – were either damaged or destroyed.

A house between East and West

It was Yugoslav partisan movement that raised during the tragedy of war, fought against Germans and domestic collaborators and finally liberated the country, with a little help from Soviet friends and comrade Stalin, though. The deal was mainly arranged during the Yalta conference. Churchill, as Bismarck before, didn’t think that Balkan was worth enough to sacrifice British soldiers, but Soviet soldiers, many of them, died for it.

Germans were beaten, the monarchy was abandoned and Belgrade became the capital of the Socialist Federal Republic with comrade Tito on its head. Just a few years later, in 1948, comrade Tito would tell his ”historical no” to comrade Stalin. Yugoslavia broke with the Soviet Union, for real. That was a ”Copernican turn”.

Today, many students of the Faculty of Mathematics in Belgrade don’t know that the monumental building of their faculty, built in the early 1950s, has the shape of the word ”No” (”Ne” in Serbo-Croatian). The ”middle finger” was supposed to be seen from the air. From the perspective of comrade Tito and Yugoslavian comrades, it was necessary to underline that they showed the finger to Stalin and that they survived doing it. ”Something in-between” East and West became the ideological ground on which ”Second” Yugoslavia would be built. It was a socialist country nurturing ”workers self-management” as its’ version of socialism and democracy. It was relatively open to the market economy and very open to popular culture coming from the West. It neither belonged to the Warsaw Pact, nor to NATO; it was one of the founders and leaders of Nonaligned movement that was gathering Asian, African, South American countries which were gaining their independence, inclining to socialism, and not wanting to be part of dominant blocks.

As the country was over-killed and dismembered, its’ peoples lost the voice. As many times in the past, an old hegemonic Orientalist narrative prevailed again. An integral part of that Orientalist approach to Yugoslavia is that it was a part of East block and dictatorship. Besides being factually wrong and arrogantly dismissive, the narrative on Yugoslavia as ”Eastern European dictatorship” is just causing misunderstanding and non-understanding.

That dioptre can’t provide anything but a very twisted, simplified and at the end – the wrong perception of reality. Such perceptions then lead to wrong policies, and instead of solving anything, problems just mutate, grow and multiply. That’s exactly how the army of Western sham-experts have been solving the Yugoslav crisis in the last 25 years. ”Putting out the fire with the gasoline…

Capital of Yugoslav modernity – Growing up in the dictatorship

I had a privilege to grow up during the golden age of Yugoslav ”dictatorship”. It was a good time, the best in my life so far. Just because of the fact that most people around, all over the place, were satisfied. It was a modest life, but the point was that everybody could afford basic human decency.

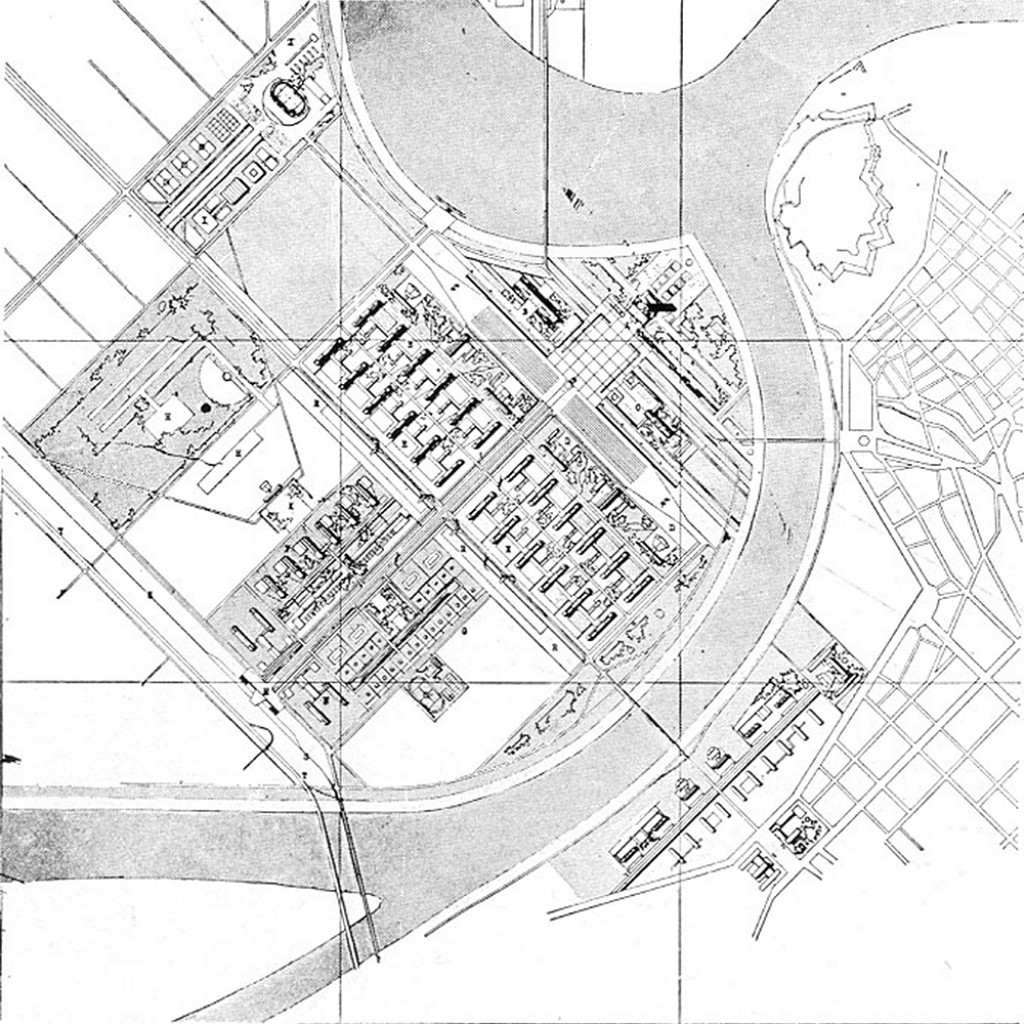

The symbolic emanation of the whole era was New Belgrade, ”capital of Yugoslav modernity”. It’s a whole city (that has 215 thousand inhabitants today), built after the Second World War, by massive ”youth work actions”, in a piece of land that used to be a swamp. It was created according to ”the most modern principles of urbanism”, as one promotional film was claiming.

In practice that meant a Yugoslav reading of Le Corbusier’s Athens Charter – modernist functionalist urbanism– ”an approach that transcends national boundaries, developed collaboratively by an international group of architects”. In a recent study ”Designing Tito’s Capital: Urban Planning, Modernism, and Socialism in Belgrade” Brigitte Le Normand basically proves that even in terms of city planning Belgrade and Yugoslavia were not following centralized, Soviet-style pattern, but rather decentralized one which had much in common with Western approaches of the time.

New Belgrade was the main symbol of Yugoslav modernist concept in urbanism, but the similar concepts of housing were applied in many other ”suburbs” – Banovo brdo, Julino brdo, Miljakovac, Šumice, Konjarnik, Cerak…

I grew up in Banovo brdo – Ban’s hill, a simple decent middle-class suburb that grew in an area where Matija Ban (1818-1903), a poet from Dubrovnik who was the first to use the term ”Yugoslav”, in a poem from 1835, had his mansion. In Matija Ban’s time that was a forest away from town; six, seven decades after his death, Banovo brdo was becoming an interesting mix of small family houses and ”socialist” buildings.

In that time the practice was that people would get flats through their enterprises. They would actually get the ”tenant’s right”, since flats were not considered as private property. My father got his flat as a 30 years old journalist in the daily newspaper. Other neighbours in our four floor redbrick building were workers from the heating plant, musicians from philharmonic orchestra, drivers of public transportation buses, post-office clerks, opera singers, mechanics from the railway. All flats were more or less identic, two rooms, kitchen, bathroom, balcony. There were no significant social differences between residents. There were no poor ones, nor particularly rich ones. Each flat still was a world per se.

Kids from the building were growing up together. Nikola, Rade, Armin and I were the crowd from the same ”entrance” – Rade and Armin were on the ground level, Nikola and I were on the first floor. I was the youngest among four which was not always fun. There was a whole bunch of other kids in the block. We were out all the time – running around, playing football, hide-n-seek, ”partisans vs. Germans”… For some time we were playing cricket also. It was introduced by, Ben and Damian, two British boys whose parents were renting a house in the neighbourhood.

That bunch was always together. Literally. By entering each other’s flats, we were entering to very different worlds and ”civilizations”. Sometimes it was not necessary even to enter the other flat. Đokićs, opera singers from the second floor, were rehearsing regularly in their flat. So, everybody in the building was, willingly or unwillingly, attending the opera.

In my class in the school, there were Roma kids, whose parents were working as carriers in the railway station, or selling plastic bags in the local green market, and there were also kids of some of the top state officials. We were brought as equal, and as friends. As long as I’m concerned, that was the main point of education.

There were, oh yes, ”clashes of civilizations”. It certainly was unpleasant and painful sometimes, in a similar way as it must be today for kids in my suburban ’hood’ in Stockholm – their parents came from all over the place, speaking different languages, believing different gods, and they are supposed to find the common ground with their neighbours and classmates. In our case, in the end, different ”worlds” and ”civilizations” would usually find the common language. Good mannered boys were picking up vagabondish manners from the vagabond ones. And vice versa. Both were learning to swim through different milieus and to communicate with very different people.

In the time of Yugoslav ”dictatorship”, Belgrade was to a great extent created by buildings as this building of mine in Banovo brdo. Many such buildings – the people that were living in them and lives that they were living – was creating a middle-class society. In Belgrade and all over the space previously known as Yugoslavia.

In Ljubljana, Maribor, Rijeka, Split, Dubrovnik, Herceg Novi, Kotor, Zagreb, Sarajevo, Mostar, Tuzla, Zenica, Subotica, Novi Sad, Kragujevac, Niš, Skoplje, Bitola… They had different pasts, but also the moment of the common present, marked by the idea of equality, social justice, progress… According to the ”spirit of the time”, the progress was for quite some time equivalent with industrialization. It meant the construction of new factories and massive migration from rural areas towards new, industrial city centres.

As Belgrade was the biggest ”star” in that constellation, the biggest number of people from all over Yugoslavia and elsewhere were coming there – to study, work and visit. Many of them were staying, some for good. That’s how Belgrade was becoming the first urban and cosmopolitan experience to many, as well as Yugoslav melting pot. And, not only Yugoslav, thousands of students from non-aligned countries were coming too, from Syria, Libya, Palestine, Ghana, Kenya, Zambia…

The culture was assumed as important; music, film, the theatre was blooming. In 1965, The Museum of contemporary art opened the first one within the socialist world. In 1967, Bitef, the most cutting edge theatre festival during the Cold War, had its’ first edition. Jerzy Grotowski and Bob Wilson were meeting there, and many others. In 1971 there was the first film festival FEST. My mom was sitting next to Jack Nicholson in cinema Kozara, during one screening in an early FEST. She was repeating many times how surprised she was to realize that he was so – short.

People had perspective. They didn’t feel shorter than celebrities. High aspirations on personal and general level existed. Marina Abramović is probably globally the best-known offspring of that atmosphere and ”spirit”. She was a child of New Belgrade that grew up in and around ”SKC” – Student Cultural Centre – one of the epicentres of creative energy.

But she was just one person in a big crowd of interesting, talented, creative people who were striving high and had the world as a referent point. Virtues of Belgrade that are still surviving, as immediacy in communication and (now relative) safety, are the heritage of such a society.

Why, oh why…

”If it was so good, why did it end?”, is a logical question. One song and one proverb come to my mind as answers: ”Too Good Be True” and ”All Good Things (Must) Come to an End”.

There are thousands books written in last two decades trying to provide the answer to the question ”Why, oh why…” Whoever is curious and willing to search for that answer, there is plenty of stuff to read. Finding an OK explanation could become a lifelong task, though. So, I won’t elaborate that here. I’ll just try to conjure up how the unrolling of Yugoslav tragedy looked from Belgrade’s perspective. I mean, from the perspective of a citizen, not a political body. In the time to come, Belgrade would be too often denominated to one political crew.

When I try to recall the signs of crisis in the ’80s, from a child’s viewpoint, all I can think of is a shortage of certain products, as coffee and detergent. In one period, probably in 1981, there were also power cuts in the city for some time. That was boring when it would happen at home, but in school – it was fun.

However, there is one big urban mess on the edge of Belgrade originating from the same period. In a piece of agricultural land belonging to the village called Kaluđerica, on the east side of the city, an illegal settlement started to grow, rapidly. Newcomers from the province were coming to Belgrade to work, there was no available housing for them, and ”wise” villagers started to sell agricultural land piece by piece. Newcomers were buying it and building houses there, without permissions and without regulated infrastructure.

Since there was no ability to provide enough flats, authorities were pretending they did not notice anything. Little by little, Kaluđerica became the biggest, or at least one of the biggest, illegal settlements in Europe appeared – ”suddenly” – as a town within the town. The problem was let to grow too big to be solved in a proper way. Kaluđerica is a very picturesque metaphor of the inability of the system to deliver. More precisely, that was primarily the inability of the system to admit the existence of the problem until too late. On one hand, the ideological lenses were too strong to face the uncomfortable realities. On the other, there was no clear idea about the right way to go.

It was not just a Yugoslav crisis – the paradigm of industrial society was becoming out-dated and the welfare state was losing its founding ground in a wider context. It happened to Sweden as well. However, as a complex multi-ethnic state composed from the leftovers of different empires, Yugoslavia was just much more vulnerable than others.

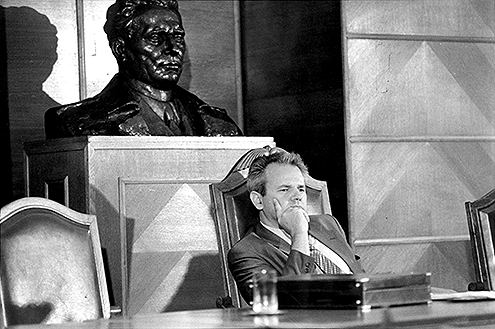

As a 15-16 years old teenager, one usually doesn’t care much about politics. That included me as well. Politics looked boring to me and I didn’t bother. I remember well, though, my father’s deep concern after one political session broadcasted on television. His comment was ominous: ”Whoever comes to power in such a brutal way as this will certainly get dethroned in a similar manner. I’m just worried about what will happen in the meanwhile.” That was September 22nd, 1987, the day that Slobodan Milošević would basically take the charge of Serbia.

Unable to face the real challenges – how to restructure the economy for the already approaching post-industrial age, stupid kitchy nationalism was established into a new source of legitimacy of the ”power elite”. In the Yugoslav context, that had an effect as of a galloping cancer cell. It didn’t take long until the conveyor belt of disasters began. In the ”first act” Belgrade, and other cities as well, were abused as scenography for staged ”rallies” that were basically nurturing very vulgar intellection of the nation. In the same time, they had a domino effect.

Nationalists rise all over the place in the space previously known as Yugoslavia; (un)surprisingly they receive legitimacy from the West. That was the time when West was praising every anti-communist idiot as a great democrat. Voices of reason, acting from a Yugoslav standpoint and trying to keep the country together, were being shut by new national(istic) elites and ignored by the West. A Tsunami wave could be seen on the horizon. However, many were still on the beach, sunbathing. People generally didn’t believe that an immense catastrophe could happen ”50 years after the Second World War”.

In the second act ”War is in the air…” Unthinkable things become everyday news. Horror begins. Attaching all the blame for it to ’Belgrade’ becomes very common in the ’good guys vs. bad guys’ pattern. Therefore one simple fact has been overlooked for years in reporting and reflections on Yugoslavia; the evasion of mobilisation in Belgrade was extremely high. People, at least the ones of my generation, didn’t want war and didn’t want to go to the war. Fortunately for many, Belgrade was big enough to provide secret shelters. In smaller towns that was not possible.

Then events speed up. Coffins start to arrive. Borders are being closed. Long isolation begins. Stigmatisation. Sanctions. Refugees. Thousands and thousands of them. Hyperinflation – banknotes with 10, 12, 15 zeros. Salaries of 5, 10 German marks. Empty shops. Buying gas in the street, in plastic Coca-Cola bottles. The collapse of public transportation. Hiking and hitchhiking to faculty and work. Long lines in front of embassies. Buses to Budapest – to the nearest airport. One-way tickets…to Canada, New Zealand, wherever. Crowded trains to flee markets in Hungary and Bulgaria. Smuggling to survive. Selling staff on paper boxes and car hoods’…

In the urban space added floors on already existing buildings become an architectural mark of the time. Those ugly miss-deeds are one of the visible scars of that decade. Poverty becomes tangible. Demonstrations became a way of life. Not only to me.

The third act starts with the NATO bombing. Then an ”orange revolution” before the Orange revolution follows. In fact, that was just a soft coup d’état supported and approved by the West. ”Democracy” won. It opened the gates for neoliberalism. The end. Of history.

Those were my twenties. I would lie if I would say that there were no joy and happy moments during that time. There were. But, there was always a shade. Of disappointment, sadness, hopelessness. When I think about Belgrade in that time the first image that comes to my head is decline, as well as feeling of claustrophobia. I was sharing the criticism of the EKV’s song: ”This city was throwing its’ light far away, this city could have done it better…”, but also it’s’ faith that ”the day is coming…”

The overcool new Berlin

One and the headline that I read lately in several Western media, from Guardian to Dagens Nyheter was: ”Belgrade – new Berlin”. Every time I see it, I react as the first time: ”Wow, I must visit that city! How can I get there?” It’s easier and more pleasant to have the image of a cool arty-party town than of the cradle of evil, that is for sure. Still, there is one riddle in all that labelling and branding that has to be solved. How come that a city which was labelled as the cradle of evil overnight becomes an overcool new Berlin? Was it really that evil as it was labelled by free and objective Western media or was ”exorcist” so successful that it became so cool so quickly after being so evil?

The other issue is the meaning(lessness) of ”new Berlin”. One writer noticed well that ”new Berlin” became ” shorthand for an under-visited European city that is cheap, fun, and up-and-coming”. In other words, there are many of those ”new Berlins” that one can easily lose track.

Berlin’s ”cool” originates from a peculiar moment of city’s unification when, for a moment, it looked like that ”another world was possible”. In the meanwhile government and politicians moved in, together with whole their ’entourage’. Since then a permanent gentrification process has been going on, and the ’spirit of the city’ changed. It’s still a great city, but not so edgy as it used to be, though.

However, the image of Berlin as cool still sells well; so well that it sells ”New Berlins” also; just for city breaks though. I know first hand how that narrative has been produced by so-called travel journalists. Their journeys are usually not arranged by their own media, but by tourist agencies and tourist organizations. Their job is more or less to have fun – to stay in good hotels, eat in good restaurants, go out, drink cocktails, and “feel the vibe”… Even if they would have time for getting out off the beaten track, editor in chief would not publish their ”serious” story. Therefore, they don’t even bother…

Paradoxically, although they are considered as ”light category”, in case of Belgrade these journalists, who were coming in the last few years, really brought a certain discursive refreshment. Completely unconsciously, as the political realm is beyond their understanding, they challenged and to a certain extent even changed the malignant, dehumanizing and racist stereotype, created by their editors in chief and ”serious” colleagues covering politics and international relations.

Alas, that was done by creating another pretty fictional image! Still, one must wonder how come that this new image of Belgrade is so arty-party positive. Is it all about the paid plane tickets, fancy hotels, good food, massages and particularly good ”Sex on the beach”? It must be so to a certain extent, but it’s not only that. It’s more about ”culture shock”.

When a mainstream mind, shaped by (Western) mainstream media, comes to the place which was repeatedly, for a long time, presented to the general public as the cradle of evil, as was the case with Belgrade, the first reaction must be: ”Wow, there are some humans here, not only evil monsters… as my editor in chief was writing in his days of glory.”

Furthermore, when they find a vibrant and lively place with plenty of venues to eat, drink, socialize any day in the week, any time of the day, it’s a pleasant surprise, but still confusing. They come to cradle of evil and they encounter something… well, something that they can’t really explain.

Then they stick to ”new Berlin”. That’s a safe ground, because it’s fluid. It can mean anything, and connotation is positive. Regarding Belgrade that is a subversive script for Western media – it is too benevolent to ultimate bad guys and the cradle of evil.

New Bagdad

One little detail makes Belgrade absolutely unique in Europe. Alas, it is seldom or never mentioned, in the arty-party ”New Berlin” bubbling. Belgrade had the special honour to be the first and only European capital being bombed by NATO. It happened without the approval of the UN Security Council, but in the name of democracy and human rights. It was a bombing that destroyed cultural heritage of first grade, as master-pieces of modernism by Nikola Dobrović and Dragiša Brašovan, were demolished by supreme forces of good, in the name of ultimate and unquestionable good.

That’s why Belgrade fits the most to the company of Bagdad, Damascus, and Tripoli, really bad cities that had to undergo the process of a democratic exorcist. Although Bagdad or Damascus are ancient cities, much older than Belgrade, all these cities share a common recent experience of extreme stigmatisation. They all deserved to become legitimate targets in the struggle of ”forces of good” against ”forces of evil”. Interestingly, they also used to be capitals of complex states that were secular, independent or wanna-be-independent, and not unconditionally inclining to neoliberal capitalism as the only form of ”democracy”.

In their cases, i.e. in cases of collective guilt attached to all the people living ”by chance” in certain places, exceptions are made to the universal principle that everybody is innocent until proven guilty. Privilege to be excluded from such a universal principle really makes you unique and special. And provides a unique and special view on humanistic principles shaping today’s world – cities, states, continents… On democracy and human rights.

Belgrade became, therefore, a unique European and global symbol of ”new democracy” established by a democratic exorcist. The city that was during the ”dictatorship” designed for egalitarian in its’ new ”democratic” incarnation has been upgraded to old, i.e. classic Latin American social structure. The city is improved by the creation of segregated areas for the filthy rich ones – separated, fenced, guarded… And fancy private schools for their kids.

The free market has been regulating that poor ones serving the rich get off far enough, where they belong. Social situations as ones from my building in Banovo brdo and my school have gradually become more and more impossible. What used to be one city for all has been transformed into several parallel worlds, which are not supposed to intertwine.

Big dirty money has been promoted into the main city architect and urban planner. There’s no money dirty enough not to be legitimized and washed by a number of international banks (in new democracy domestic banks don’t exist).

Whole neighbourhoods with smaller family houses with gardens are being erased by mafia-style contractors, i.e. entrepreneurs. They build whole blocks of ”Kaluđerica style” buildings – without proper papers, plans, and infrastructure. Those trivialities are arranged later, all in the name of entrepreneurship. There is no architectural and construction monster that can’t be legalized. That’s the dominant urban, architectural and social vision.

Concepts of the public good, public interest and public space have been abandoned. In new democracy that’s outdated. It’s nicer, more modern, more democratic and more European to have shopping malls instead of parks, to have parking space instead of playgrounds for kids, to build big kitschy churches instead of schools and hospitals… Shopping malls have been established into a symbol of beauty, good, and progress; there’s no other aesthetic idea, the vision of the future. The shopping mall doesn’t have any alternative.

There is also another paradigmatic ”monumental symbol” of a new time and democratic values established in Serbia. The statue of Haidar Aliev. Globally famous democrat from Azerbaijan is posted in the most beautiful and most central park in Belgrade – Tašmajdan. It was opened by the highest state and city officials from the, by then, ruling Democratic Party, which is, by the way, a sister-party of Swedish Social Democrats and one that is still receiving support by Olof Palme Center. The message to citizens was as clear as clear can be – in democracy anything goes, if enough cash is cashed.

”History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce”, is an often-quoted Karl Marx’s sentence. In the case of Belgrade and Serbia, it’s not even farce anymore. That’s boratesque. ”Borat in Serbistan” has many sequels. ”The show must go on…”

The latest and most grandiose boratesque project is called ”Belgrade Waterfront”. The aim and the big vision is to build little Abu Dhabi on the bank of Sava River. While the city is chronically incapable to solve its’ huge problems with basic infrastructure – with housing, awful traffic and public transportation, the collapse of social services, facades that are falling apart, noise, pollution, storage of waste – a bunch of Borats running the place are building the city of skyscrapers on the city’s most precious piece of land. The shady project, whose details are kept as a secret, is imposed by ”lex specialis”; without any public discussion, despite serious arguments by associations of architects, with suppression on any critical question on the issue… In the age of socialist dictatorship something like that would be unthinkable. In new democracy even if someone would try to question dubious decisions by authorities, freedom of expression progressed so much that there’s literally no place where it would be possible to do it. Not a single reliable media exist where to publish critique of boratesque practices.

I’ve got to the point that it became easier to be anywhere else in the world than in Belgrade. It has been too painful, frustrating and sad to watch how valuable things are being ruined or just let to deteriorate, how honest, intelligent, and valuable people wither, how I myself wither, and still being completely disempowered to change anything.

”People in Belgrade are sad”, my Swedish Syrian friend Bassam Kabeir says. He passed through Belgrade recently, as a refugee. Knowing it from the mid-eighties, when he studied engineering there, the new reality was striking to him. Faces of people were happier in the time of ”dictatorship”. But, happiness is not a relevant category for analyse and judgment, right?

After All

After a turbulent century, Belgrade is kind of back where it was a hundred years ago – it is the capital of Serbia, which is now having around 7, 5 million people. Just kind of, because we live in a completely different world today. Even 19th century ”romantic” nation-state concept, that countries of former Yugoslavia, including Serbia, are tied in, isn’t romantic anymore. Quite the opposite, it’s much more closed, rigid and claustrophobic than it was in the 19th century and it’s actually functioning as a straitjacket. Peoples who were in the 19th century seeing each other’s as brothers to connect with are now seeing each other as enemies not to communicate with.

Moreover, a permanent state of schizophrenia has been established in the area by the so-called international community. There’s no international law and universal principle, which wasn’t violated and broken in the name of some higher good. So many exceptions from the universal principles had been made, as the goal was to create a permanent state of controlled instability.

As a consequence, the whole that space-area-region, however we call that territory, remain fragmented, undefined and stuck. Administrative borders have been changing many times and it seems that they will be changing again. New conflicts and wars are not excluded either.

Major administrators and high commissionaires from European ”top(s)” don’t bother much. Their main concern has always been just to keep their non-taxed high salaries; in that sense, controlled instability seems to be a perfect solution.

20 years after Second World War, which was much more devastating in every way than conflicts and wars of 1990’s, Yugoslavia made a huge progress; until 1960’s a radically new reality was created. More than 20 years of European Union’s administering, that whole space-area-region is nothing more than a hopeless dump; everybody having any opportunity is leaving.

Former Yugoslavia, Western Balkans, South-Eastern Europe, post-Yugoslav sphere, the jumble already starts with the name. What it really is, where does it start, where does it end, what it is supposed to be? It’s an area of great confusion, first of all, completely unclear as a whole. ”Out of focus” similarly as Robin Williams in Woody Allen’s ”Deconstructed Harry”.

In the centres of European Union, there’s no interest, willingness and ability to integrate that region into European Union at all, and particularly not under conditions which would provide basic decency and prosperity to ordinary people. That region is rather seen as a handy neighbourhood dump for toxic trash.

Current local elites there are more than happy with the role of dump managers. Their sight and vision don’t go further than that anyway; for them, even mediocrity is unconquerable hight. So, in the current setting the circle is closed. This way or another, the state of that whole space, its’ ugliness and hopelessness, is the illustration of the dead end of the current ’European way’.

Surprisingly or not, potential ’exits’ are the same as elsewhere around Europe. One is well known – a deja vu from the 1930s. The other might lead somewhere else than to dead-end. Despite all their weaknesses, movements as for instance Barcelona en Comu around Ada Colau provide a bit of hope.

In the space-area-region previously known as Yugoslavia there are some similar heralds. And guess what – they are not waving with ethnic flags. Eureka! These voices are still weak, but the mood ripens. Somehow I have the same feeling as Lars von Trier – ”planet Melancholia” is to hit soon; the reality founded in unsustainable human behaviours, relations, lifestyles will be swiped… I’m looking forward to that day. I just hope that it will be on the weekend. To celebrate it together with Croats and Slovenes. With few beers in one of Belgrade’s bars.

Then what?

Then, hopefully, we will get to the ground zero – to the opportunity to create ourselves the environment we want to live in. Such a task would require moral vision and bravery in imagination, as Lewis Mumford would put it. The greatest bravery and imagination will be to think outside of the given ’end of history’ frame; to think as creators, not as reproducers.

More than half of the world’s population is living in cities already. If the current trend continues around 2050 three-quarters of the world’s population will live in cities. That makes ’a sustainable city’ an essential precondition of sustainable future. What kind of city, and what kind of society, could provide such a future, for all?

That’s a question that all citizens, wherever they live, should have thought, as well as a say. The right to the city, i.e. the freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is also a human right, as David Harvey claims. We live in the age and in the world where challenges went far beyond national borders. Therefore, if challenges are to be dealt, it’s necessary to act the same way – beyond national borders.

For instance, through regions defined around one or several cities. In such a wider context I could imagine huge walls of distrust going down and prosperity moving into that space previously known as Yugoslavia.

When I imagine it prosperous, I imagine it as a constellation of reshaped sustainable and prosperous urban ’stars’ that shine around, with creativity, openness, cosmopolitism, and whose lights are intertwining, enlightening wide space.

However we decide to call it in the end, that space there is not only a simple bridge, but it’s also a pike connecting Europe, Mediterranean, Middle East, Turkey, Russia. It needs, therefore, to be polyphonic, polycultural, polyglot. A lot of skills would be needed to manage such a complex and requiring task; there is so much to learn and do.

Still, one must keep on mind that “historical experience” of that space is such that “worst scenarios” are quite common, usual and possible. Today’s reality of Belgrade, unfortunately, resembles very much to one such scenario. I would like to believe that damage that has been done to the city is not irreversible. Let it be what it can’t be.

Predrag Dragosavac

predragdragosavac@gmail.com

Predrag Dragosavac is a journalist, writer and ’professional media observer’. Born in Belgrade, living lately in-between places and realities as a ”digital nomad” (kind of). Predrag Dragosavac has covered popular culture in the daily newspapers, hosted radio shows, reported from the Balkans, USA, Brazil, Norden and the Baltic states. He was during several years part of the Global Bar team, bringing the concept of Global Bar to environments where there are no real bars and even fewer dialogues.