ANALYSIS. Diplomats tend to avoid risks and settle for partial results. But for Swedes imprisoned in Iran, China and Eritrea, this is a disastrous approach, writes Susanne Berger from the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights and Caroline Edelstam from the Edelstam Foundation.

This is an analysis. The opinions expressed in the article are those by the authors.

If the Swedish Foreign Ministry were a country, it would rank among the most isolationist, least participatory societies in the world.

Years ago, during the official investigation of the fate of Swedish diplomat and Holocaust hero Raoul Wallenberg in Russia, researchers would huddle to discuss how to move the inquiry forward. The group felt that if they could just convince Swedish officials to tackle the issue in more creative ways, to seek answers from unexpected sources, such an approach could yield important progress.

It took years before the realization finally set in that the seeming foot dragging by Swedish diplomats was not due to a lack of understanding, a failure to recognize the value of the proposed steps, or obscure bureaucratic hurdles. They simply did not want to act.

This institutional aversion towards cooperating with outsiders has proved to be a major obstacle in the handling of current cases of Swedish citizens missing or arbitrarily detained abroad. Swedish officials prefer to deal with politically sensitive matters strictly “in house”, keeping their cards tightly to their vest and any third parties firmly at bay, even when seemingly at their most openminded and inclusive.

An inherent conflict of interest

Above all, family members are experiencing firsthand how much the Swedish Foreign Ministry has closed itself off not only from them, but also from any outside scrutiny. Representatives of the public – human rights advocates, journalists, even parliamentarians or legal counsels – are kept at arm’s length. Obfuscation, evasion, delays, the feigning of ignorance are all tools to avoid direct interaction and cooperation. When this fails and Swedish officials feel pressured, they resort first to anger, only to shut themselves off even more, by not responding to inquiries or invoking Sweden’s strict secrecy provisions.

Representatives of the public – human rights advocates, journalists, even parliamentarians or legal counsels – are kept at arm’s length.

Both families and their advocates emphasize that they do not want to take an adversarial position. In fact, they want nothing more than for Swedish officials to succeed. None of this appears to register or bring about any meaningful change.

Part of the problem is, of course, that Swedish diplomats primarily represent Swedish national interests which creates an inherent conflict. It means that the goals of families and those of the Swedish government do not always coincide. Families have only one aim – to free their loved ones. Diplomats have many other factors to consider which makes them naturally risk averse. It also makes them far more inclined to accept partial solutions.

Avoiding collateral damage

Since the end of the Second World War, the Swedish government’s more or less unilateral approach – both in the international arena and at home – has registered some important successes. But the overall record of unsolved cases and desperate families remains dismal.

It begs the question if a full resolution of pending cases would bring revelations or any negative publicity that the Swedish government would prefer to avoid. This may well be a factor in some of the continuing Cold War era investigations, like the Soviet downing of a DC-3 aircraft in 1952 with eight (possibly nine) men on board; the Raoul Wallenberg inquiry; the loss of more than a dozen Swedish ships with 100+ missing sailors; or the still unsolved 1961 death of UN General Secretary Dag Hammarskjöld; and, more recently, the murder of Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme in 1986, the various foreign submarine incursions into Swedish territorial waters; and the 1994 MS Estonia ferry disaster which left 852 people dead. Hence perhaps the readiness to settle for incomplete results.

It is not like Swedish officials lacked important leverage in these inquiries – yet they repeatedly refused to employ it. For example, in 1963, the Swedish Security Police (SÄPO) detained one of the Cold War’s most important Soviet agents, Swedish Air Force Colonel Stig Wennerström, but the government repeatedly failed to press its advantage with Soviet authorities. The same happened in 1981, when a Soviet submarine and its crew were stranded in Swedish territorial waters.

A narrow political calculus

Swedish officials generally follow a longstanding government policy of not linking two separate issues – unless, of course, it suits them. The most recent example is the feckless deal Sweden struck with the Islamic Republic of Iran while holding a huge trump card in the form of the former Iranian official Hamid Nouri. Nouri was arrested and sentenced to life in prison in Sweden in 2022 for his role in the mass executions of thousands of political prisoners in Iran in1988. His sentence was upheld in December 2023.

Swedish officials either did not understand or ignored Nouri’s enormous value to the Islamic Republic. Instead, they cut a limited deal, leaving a Swedish citizen – the physician and medical scholar Dr. Ahmadreza Djalali – and possibly a whole slew of other European and foreign hostages behind in the process. The decision appears to have been mainly a political calculus. After Mr. Nouri’s detention in 2019, an exchange of Nouri for Dr. Djalali was never even considered. In fact, there was a debate whether Swedish law actually permitted it.

Djalali was detained by Iranian intelligence agents in 2016, accused of espionage. He was sentenced to death in 2017, in a sham trial. He has denied all charges. Nevertheless, only when Swedish EU diplomat Johan Floderus ran into trouble in Iran in 2022, did Nouri’s return all of a sudden become a serious subject of discussion and Sweden quickly proposed an adjustment of its legal code. Ultimately, the Swedish government decided to solve the issue by granting clemency to Mr. Nouri, a purely pragmatic and highly controversial decision.

It is quite obvious what prompted the Swedish government’s change of heart: If Mr. Floderus had gotten seriously injured or died while imprisoned, the political price at home would have been steep. In the case of Ahmadreza Djalali not so much. Leaving aside the question if a convicted mass murderer should have been freed in the first place, the Swedish government’s action revealed a glaring double standard regarding dual nationals like Dr. Djalali, not to mention the fact that its behavior constituted a clear violation of the equal treatment of Swedish citizens before the law.

The Prime Minister ignores official correspondence

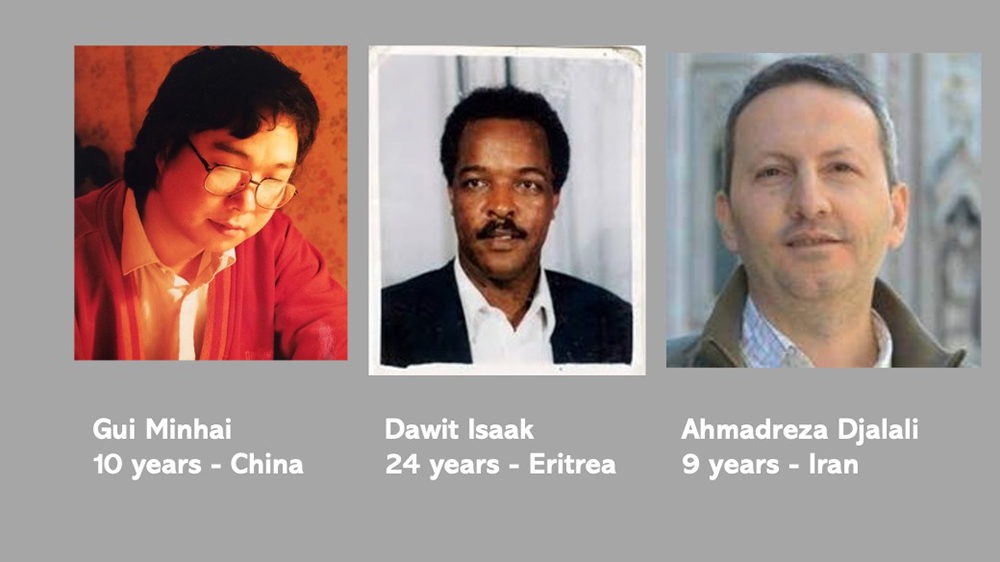

Since Johan Floderus’s safe return in 2024, Swedish diplomats have fallen back into their old familiar patterns. They act when pressed, but do not seem to maximize efforts to bring about the release of Dr. Djalali or the other two long-held Swedish prisoners abroad – the Swedish Eritrean journalist Dawit Isaak, imprisoned in Eritrea for close to a quarter century now; and Swedish publisher Gui Minhai, who has been detained in China since 2015.

Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson’s office has not responded to a letter sent to him by 22 former hostages in Iran in May 2024. The letter urged Mr. Kristersson to avail himself of the opening created by Iran’s Foreign Minister Seyed Abbas Araghchi’s public criticism of Sweden, voiced a few weeks earlier (in a post on the social media platform ‘X’). Araghchi pointed out that the Swedish company Mölnlycke in 2023 stopped deliveries of highly specialized medical dressings (Mepilex) to the Islamic Republic. The dressings are urgently needed to treat the blistering wounds created by Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB), a rare genetic skin condition, affecting more than a thousand Iranian children. Interestingly, in 2022, the Swedish government actually provided 1.6 million Euro (SEK 18 million) to UNICEF to facilitate the continued deliveries of Mölnlycke’s products to the Islamic Republic. It is not known if Sweden received any concessions from Iran for this humanitarian gesture.

Despite numerous follow up inquiries, it is entirely unclear how exactly the Swedish government has acted on the former Iranian hostages’ proposal which has the potential of not only freeing Dr. Djalali, but other foreigners imprisoned in Iran, including EU and U.S. citizens.

Expanded ties with the U.S. government, via the U.S. military’s purchase of Saab’s Giraffe 1x radar systems worth $46 million, and the recently concluded bilateral agreement on technology safeguards, which grants the U.S. access to Swedish spaceports for commercial satellite launches, means vital diplomatic channels exist to address shared concerns. U.S officials and (American) legal experts have repeatedly offered their full support. As time ticks by, Sweden may well be losing a critical competitive advantage, with Iran attempting to meet the need for Mepilex through its own domestic production.

A submission by members of Raoul Wallenberg’s family has been left unanswered since April.

Meanwhile, Mr. Kristersson’s office has failed to acknowledge two formal letters submitted by Djalali’s legal counsels. Their client’s health is declining and remains critical. The Swedish Foreign Ministry’s consular department has refused to answer a list of detailed questions submitted by Dajali’s wife back in September, citing secrecy restrictions. The decision to sidestep controversial subjects is not only evasive but appears to be part of a new policy: A submission by members of Raoul Wallenberg’s family has been left unanswered since April.

Here too, the calculation, seems clear – public pressure regarding Swedish citizens missing or imprisoned abroad remains relatively subdued. Demonstrations at home or other initiatives on their behalf rarely attract more than a handful of people, so the government sees little cause for stepping up its engagement.

A profound lack of urgency and political will

Swedish officials apparently consider their efforts to urge the Iranian leadership not to carry out Ahmadreza Djalali’s death sentence a success in itself. Not surprisingly, his family feels that the Swedish government can and must do much more to secure Dr. Djalali’s release, given the almost unimaginable physical and psychological torture he has endured over the past nine and a half years.

This past May, the Islamic Republic News Agency reported that Sweden is exploring expanded trade ties with Iran. The hoped for deal supposedly centers around the automotive and industrial sector, especially “heavy vehicles, energy generation, telecommunication, steel and mining.” It is unclear how the European Union (EU) and other international partners feel about these plans that do not seem to involve any pre-conditions or concessions on human rights issues by the Iranian regime. It is equally uncertain if Swedish officials will condition any normalization of relations with the Islamic Republic on its release of Dr. Djalali.

Cases of political prisoners held by powerful regimes like Iran and China obviously pose enormous challenges. Nevertheless, one would think that during the span of two decades, Sweden and the EU would have found a way to confront Eritrea, one of the world’s poorest and most repressive countries. In the case of Dawit Isaak, Sweden seems to have received fairly regular assurances from Eritrean officials that he remains alive and imprisoned. Yet this news apparently has not resulted in intensified efforts to obtain a verifiable proof of life or secure Mr. Isaak’s immediate release.

This stalemate has lasted since at least 2014 which raises the question if both sides actually prefer the status quo – for very different reasons. With potential access to the intelligence capabilities of its 26 EU partners, not to mention close allies like the U.S., UK and Israel, the Swedish government should have a reasonably good idea about Mr. Isaak’s current fate. However, so far, Swedish officials do not give the impression that rescuing Dawit Isaak remains a top priority. His situation is further complicated by the fact that Eritrea has virtually no incentive to release a prisoner who will emerge greatly aged, possibly ill, and with a story to tell that will not reflect positively on the Eritrean regime.

For 24 years Swedish officials have refused to comment publicly on Mr. Isaak’s case, threatening dire consequences for Eritrea, but never following through. Again, only when pressed by his family and human rights advocates did Swedish Foreign Minister Maria Malmer Stenergard finally issue a public statement on September 25, 2025, after a meeting with her Eritrean counterpart, Osman Saleh, demanding Dawit Isaak’s release on humanitarian grounds.

Two month later, there is no sign that Eritrea is ready to comply with Swedish demands, or that Sweden and the EU are ready in any way to directly challenge Eritrea to end Mr. Isaak’s ordeal. Meanwhile, earlier this year, EU and Eritrean officials could be seen celebrating “EU Week” in Asmara, toasting each other with champagne – all in support of “peace, security, prosperity, and universal values,” according to the EU website. EU policy regarding Eritrea focuses primarily on curbing irregular migration and securing its geostrategic goals in the Horn of Africa, placing less emphasis on human rights.

Just like in the case of Ahmadreza Djalali, the Swedish Foreign Ministry refuses to answer a list of questionssubmitted by Mr. Isaak’s family, citing secrecy considerations.

Sweden and the EU have handled the case of Swedish publisher Gui Minhai in an equally problematic way. Gui was subjected to a transnational kidnapping from Thailand by Chinese intelligence agents in October 2015. His forced confession, extracted after months of pressure and under obvious duress, was broadcast on Chinese state television. Hoping to resolve the case quietly, Swedish officials did not press Gui’s case vigorously with Chinese leaders. After Gui’s brief restricted release in 2018, Swedish officials somehow failed to place him under diplomatic protection, leading to his re-arrest by Chinese security agents. Gui’s family has not had a clear sign of life from him since then.

Hopes were high when Swedish Foreign Minister’s Maria Malmer Stenergard embarked on a surprise visit to China on October 17, 2025, the 10th anniversary of Gui Minhai detention. Stenergard emphasized that Gui’s case remains “a serious obstacle in Sweden China relations,” while simultaneously highlighting a two billion Euro investment by Swedish truck manufacturer Scania in China. If enhanced Swedish Chinese economic and trade relations will create enough leverage to secure Gui’s release remains to be seen. Even as more than 90 international human rights organizations demanded decisive action and a proof of life, Swedish officials were unable to communicate with Gui or visit him in prison during the Foreign Minister’s trip.

National interests before human rights

As China’s economic and political influence has grown, so has its intransigence on human rights issues. The European Union is far from powerless. However, its reliance on well-meaning but ineffective initiatives like ”torture free trade” or its hapless ”human rights dialogue” with China sends only one message – that China can continue to bully the EU and that EU representatives will not say what needs to be said: that mistreatment of its citizens is unacceptable and will not be tolerated. A nearly unanimous vote in the EU parliament earlier this month to demand the immediate release of Gui Minhai sent an important message but will have negligible impact unless it is followed up by concrete steps to confront China.

“Many people in Sweden and the EU want to avoid economic pain,” says Magnus Fiskesjö, a former Swedish cultural attaché in Beijing, who has led a tireless campaign on Gui’s behalf. “China has gained the power to inflict a lot of precisely such pain – because we have allowed ourselves to become dependent on them and thus open to blackmail.”

The general downgrading of human rights in favor of an enhanced political pragmatism has taken hold across the board, including the EU. As Swedish China expert Malin Oud summed it up in a recent commentary, even in relatively strong democratic societies like Sweden “there is noticeably less and less talk about values, and more about national interests.”

During a recent visit to Brussels, the first such contact in seven years, Chinese representatives flat out refused to answer questions from EU parliamentarians regarding various human rights issues (from the war in Ukraine to the genocide of China’s Uyghur Muslim minority), repeating instead Russian talking points and questioning the existence of NATO.

How to define “success”?

To paraphrase the former Swedish law professor Dennis Töllborg: To outsiders, it increasingly looks like the Swedish government is in danger of slowly committing suicide in fear of death. Worried about a negative outcome, it embraces tactics that limit the economic and political fallout while diminishing the chances of freeing their imprisoned citizens. Worse, there is no indication of a coherent approach.

For decades now, Swedish officials have clung to a policy of silent diplomacy even though it has yielded no tangible result. At this point, one must ask – what is the strategy behind this seeming contradiction? Is there a method to this seeming madness? Or is the Swedish government actually content with “failure” – does it consider the mere fact that its citizens remain alive but in dangerous limbo a success? In other words, do Swedish officials feel that this is the best they can do but are afraid to say so?

The fact that Sweden has not been willing or able to create significant international pressure and that neither China, Iran nor Eritrea have incurred any meaningful costs for the continuing serious crimes committed against Swedish nationals suggests that this may well guide Sweden’s strategic thinking, at least in part. Since 2015, the Swedish Prosecution Authority (Åklågarmyndigheten, Riksåklagare) has refused repeatedly to open a criminal investigation against the Eritrean leadership; a decision that, according to Irwin Cotler, Canada’s former Minister of Justice and Dr. Djalali’s international legal counsel, “not only undermines the rule of law but incentivizes impunity.” In other words, Sweden and the EU are not only failing their own citizens, but democracy itself.

Dr. Djalali’s fellow prisoner in Tehran for seven years, the U.S. Iranian businessman Siamak Namazi who was released in September 2023, recently stressed that while families are generally advised to stay silent, he does not agree. “You should make as much noise as possible, so that other cases do not become as bad as mine,” he said. ”You need to extract a price for not releasing us.”

As the saying goes, something’s got to give – and soon. As experience shows, the longer the cases of arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance drag on, the more difficult it becomes to resolve them. The tense stalemate between victims, the government and families is unsustainable, deeply hurtful, and unproductive. Families can handle hard facts and the truth. They also have important knowledge to share that can prove invaluable for all sides.

It is time Swedish officials put their cards on the table and treat family members with the openness and respect they deserve. Swedish lawmakers, too, have an essential role to play. If families cannot receive substantive briefings due to strict secrecy rules, then some adjustments to these laws need to be considered.

Analysts warn that the global threat of hostage taking and arbitrary detentions is increasing. Swedish citizens were recently detained in Cuba and Turkey. Sweden is recognized throughout the world as a human rights leader. It should double down and assert itself, together with its international partners, not appear timid and ineffective when it comes to its own nationals, a posture that only further emboldens the perpetrators.

Susanne Berger

Senior Fellow, the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights

Caroline Edelstam

Co-Founder and President of the Edelstam Foundation

A shorter version of this article was previously published in Swedish. You can read it here.

Read Also

|

Uppläsning av artikel

|